Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

CHAPTER VI.

Глава VI.

Pig and Pepper

ПОРОСЕНОК И ПЕРЕЦ

For a minute or two she stood looking at the house, and wondering what to do next, when suddenly a footman in livery came running out of the wood—(she considered him to be a footman because he was in livery: otherwise, judging by his face only, she would have called him a fish)—and rapped loudly at the door with his knuckles. It was opened by another footman in livery, with a round face, and large eyes like a frog; and both footmen, Alice noticed, had powdered hair that curled all over their heads. She felt very curious to know what it was all about, and crept a little way out of the wood to listen.

С минуту она стояла и смотрела в раздумье на дом. Вдруг из лесу выбежал ливрейный лакей и забарабанил в дверь. (Что это лакей, она решила по ливрее; если же судить по его внешности, это был просто лещ). Ему открыл другой ливрейный лакей с круглой физиономией и выпученными глазами, очень похожий на лягушонка. Алиса заметила, что у обоих на голове пудреные парики с длинными локонами. Ей захотелось узнать, что здесь происходит, -- она спряталась за дерево и стала слушать.

The Fish-Footman began by producing from under his arm a great letter, nearly as large as himself, and this he handed over to the other, saying, in a solemn tone, 'For the Duchess. An invitation from the Queen to play croquet.' The Frog-Footman repeated, in the same solemn tone, only changing the order of the words a little, 'From the Queen. An invitation for the Duchess to play croquet.'

Лакей-Лещ вынул из-под мышки огромное письмо (величиной с него самого, не меньше) и передал его Лягушонку. -- Герцогине, -- произнес он с необычайной важностью. -- От Королевы. Приглашение на крокет. Лягушонок принял письмо и так же важно повторил его слова, лишь слегка изменив их порядок: -- От Королевы. Герцогине. Приглашение на крокет.

Then they both bowed low, and their curls got entangled together.

Затем они поклонились друг другу так низко, что кудри их смешались.

Alice laughed so much at this, that she had to run back into the wood for fear of their hearing her; and when she next peeped out the Fish-Footman was gone, and the other was sitting on the ground near the door, staring stupidly up into the sky.

Алису такой смех разобрал, что ей пришлось убежать подальше в лес, чтобы они не услышали; когда она вернулась и выглянула из-за дерева, Лакея-Леща уже не было, а Лягушонок сидел возле двери на земле, бессмысленно уставившись в небо.

Alice went timidly up to the door, and knocked.

Алиса робко подошла к двери и постучала.

'There's no sort of use in knocking,' said the Footman, 'and that for two reasons. First, because I'm on the same side of the door as you are; secondly, because they're making such a noise inside, no one could possibly hear you.' And certainly there was a most extraordinary noise going on within—a constant howling and sneezing, and every now and then a great crash, as if a dish or kettle had been broken to pieces.

-- Не к чему стучать, -- сказал Лакей. -- По двум причинам не к чему. Во-первых, я с той же стороны двери, что и ты. А во-вторых они там так шумят, что никто тебя все равно не услышит. И правда, в доме стоял страшный шум -- кто-то визжал, кто-то чихал, а временами слышался оглушительный звон, будто там били посуду.

'Please, then,' said Alice, 'how am I to get in?'

-- Скажите, пожалуйста, -- спросила Алиса, -- как мне попасть в дом?

'There might be some sense in your knocking,' the Footman went on without attending to her, 'if we had the door between us. For instance, if you were INSIDE, you might knock, and I could let you out, you know.' He was looking up into the sky all the time he was speaking, and this Alice thought decidedly uncivil. 'But perhaps he can't help it,' she said to herself; 'his eyes are so VERY nearly at the top of his head. But at any rate he might answer questions.—How am I to get in?' she repeated, aloud.

-- Ты бы еще могла стучать, -- продолжал Лягушонок, не отвечая на вопрос, -- если б между нами была дверь. Например, если б ты была там, ты бы постучала, и я бы тогда тебя выпустил. Все это время он, не отрываясь, смотрел в небо. Это показалось Алисе чрезвычайно невежливым. -- Возможно, он в этом не виноват, -- подумала она. -- Просто у него глаза почти что на макушке. Но на вопросы, конечно, он мог бы и отвечать. -- Как мне попасть в дом?-- повторила она громко.

'I shall sit here,' the Footman remarked, 'till tomorrow—'

-- Буду здесь сидеть, -- сказал Лягушонок, -- хоть до завтра...

At this moment the door of the house opened, and a large plate came skimming out, straight at the Footman's head: it just grazed his nose, and broke to pieces against one of the trees behind him.

В эту минуту дверь распахнулась, и в голову Лягушонка полетело огромное блюдо. Но Лягушонок и глазом не моргнул. Блюдо пролетело мимо, слегка задев его по носу, и разбилось о дерево у него за спиной.

'—or next day, maybe,' the Footman continued in the same tone, exactly as if nothing had happened.

-- ...или до послезавтра,-- продолжал он, как ни в чем не бывало.

'How am I to get in?' asked Alice again, in a louder tone.

-- Как мне попасть в дом? -- повторила Алиса громче.

'ARE you to get in at all?' said the Footman. 'That's the first question, you know.'

-- А стоит ли туда попадать? -- сказал Лягушонок. -- Вот в чем вопрос.

It was, no doubt: only Alice did not like to be told so. 'It's really dreadful,' she muttered to herself, 'the way all the creatures argue. It's enough to drive one crazy!'

Может быть, так оно и было, но Алисе это совсем не поправилось. -- Как они любят спорить, эти зверюшки! -- подумала она. -- С ума сведут своими разговорами!

The Footman seemed to think this a good opportunity for repeating his remark, with variations. 'I shall sit here,' he said, 'on and off, for days and days.'

Лягушонок, видно, решил, что сейчас самое время повторить свои замечания с небольшими вариациями. -- Так и буду здесь сидеть,--сказал он,--день за днем, месяц за месяцем...

'But what am I to do?' said Alice.

-- Что же мне делать? -- спросила Алиса.

'Anything you like,' said the Footman, and began whistling.

-- Что хочешь, -- ответил Лягушонок и засвистел.

'Oh, there's no use in talking to him,' said Alice desperately: 'he's perfectly idiotic!' And she opened the door and went in.

-- Нечего с ним разговаривать,--с досадой подумала Алиса. -- Он такой глупый! Она толкнула дверь и вошла.

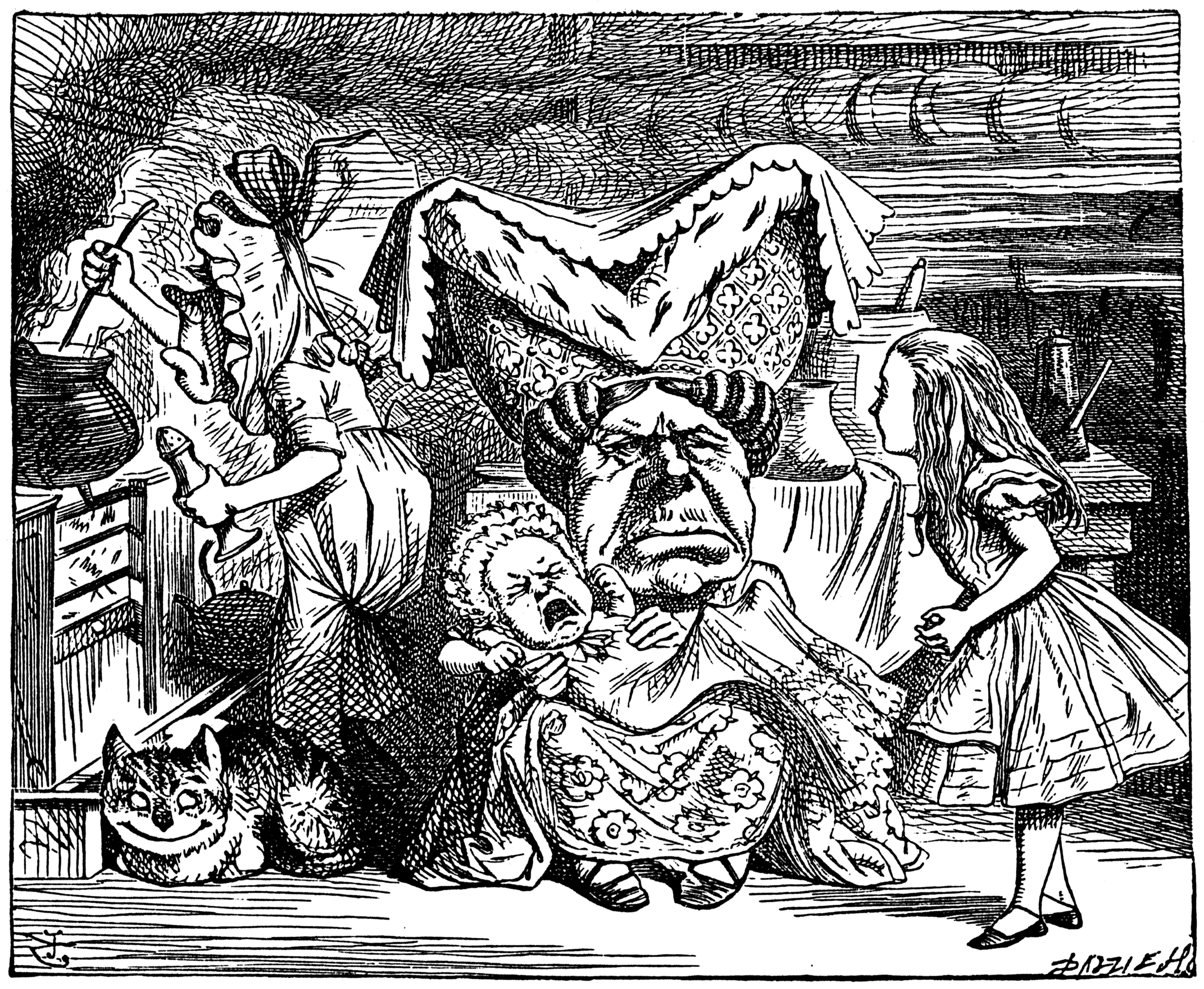

The door led right into a large kitchen, which was full of smoke from one end to the other: the Duchess was sitting on a three-legged stool in the middle, nursing a baby; the cook was leaning over the fire, stirring a large cauldron which seemed to be full of soup.

В просторной кухне дым стоял столбом; посредине на колченогом табурете сидела Герцогиня и качала младенца; кухарка у печи склонилась над огромным котлом, до краев наполненным супом.

'There's certainly too much pepper in that soup!' Alice said to herself, as well as she could for sneezing.

-- В этом супе слишком много перцу! -- подумала Алиса. Она расчихалась и никак не могла остановиться.

There was certainly too much of it in the air. Even the Duchess sneezed occasionally; and as for the baby, it was sneezing and howling alternately without a moment's pause. The only things in the kitchen that did not sneeze, were the cook, and a large cat which was sitting on the hearth and grinning from ear to ear.

Во всяком случае в воздухе перцу было слишком много. Даже Герцогиня время от времени чихала, а младенец чихал и визжал без передышки. Только кухарка не чихала, да еще -- огромный кот, что сидел у печи и улыбался до ушей.

'Please would you tell me,' said Alice, a little timidly, for she was not quite sure whether it was good manners for her to speak first, 'why your cat grins like that?'

-- Скажите, пожалуйста, почему ваш кот так улыбается? -- спросила Алиса робко. Она не знала, хорошо ли ей заговорить первой, но не могла удержаться.

'It's a Cheshire cat,' said the Duchess, 'and that's why. Pig!'

-- Потому, -- сказала Герцогиня. -- Это чеширский кот -- вот почему! Ах ты поросенок!

She said the last word with such sudden violence that Alice quite jumped; but she saw in another moment that it was addressed to the baby, and not to her, so she took courage, and went on again:—

Последние слова она произнесла с такой яростью, что Алиса прямо подпрыгнула. Но она тут же поняла, что это относится не к ней, а к младенцу, и с решимостью продолжала:

'I didn't know that Cheshire cats always grinned; in fact, I didn't know that cats COULD grin.'

-- Я и не знала, что чеширские коты всегда улыбаются. По правде говоря, я вообще не знала, что коты умеют улыбаться.

'They all can,' said the Duchess; 'and most of 'em do.'

-- Умеют,--отвечала Герцогиня.--И почти все улыбаются.

'I don't know of any that do,' Alice said very politely, feeling quite pleased to have got into a conversation.

-- Я ни одного такого кота не видела, -- учтиво заметила Алиса, очень довольная, что беседа идет так хорошо.

'You don't know much,' said the Duchess; 'and that's a fact.'

-- Ты многого не видала,--отрезала Герцогиня.--Это уж точно!

Alice did not at all like the tone of this remark, and thought it would be as well to introduce some other subject of conversation. While she was trying to fix on one, the cook took the cauldron of soup off the fire, and at once set to work throwing everything within her reach at the Duchess and the baby—the fire-irons came first; then followed a shower of saucepans, plates, and dishes. The Duchess took no notice of them even when they hit her; and the baby was howling so much already, that it was quite impossible to say whether the blows hurt it or not.

Алисе совсем не понравился ее тон, и она подумала, что лучше бы перевести разговор на что-нибудь другое. Пока она размышляла, о чем бы ей еще поговорить, кухарка сняла котел с печи и, не тратя попусту слов, принялась швырять все, что попадало ей под руку, в Герцогиню и младенца: совок, кочерга, щипцы для угля полетели им в головы; за ними последовали чашки, тарелки и блюдца. Но Герцогиня и бровью не повела, хоть кое-что в нее попало; а младенец и раньше так заливался, что невозможно было понять, больно ему или нет.

'Oh, PLEASE mind what you're doing!' cried Alice, jumping up and down in an agony of terror. 'Oh, there goes his PRECIOUS nose'; as an unusually large saucepan flew close by it, and very nearly carried it off.

-- Осторожней, прошу вас, -- закричала Алиса, подскочив со страха. -- Ой, прямо в нос! Бедный носик! (В эту минуту прямо мимо младенца пролетело огромное блюдо и чуть не отхватило ему нос).

'If everybody minded their own business,' the Duchess said in a hoarse growl, 'the world would go round a deal faster than it does.'

-- Если бы кое-кто не совался в чужие дела, -- хрипло проворчала Герцогиня, -- земля бы вертелась быстрее!

'Which would NOT be an advantage,' said Alice, who felt very glad to get an opportunity of showing off a little of her knowledge. 'Just think of what work it would make with the day and night! You see the earth takes twenty-four hours to turn round on its axis—'

-- Ничего хорошего из этого бы не вышло, -- сказала Алиса, радуясь случаю показать свои знания.--Только представьте себе, что бы сталось с днем и ночью. Ведь земля совершает оборот за двадцать четыре часа... -- Оборот? -- повторила Герцогиня задумчиво.

'Talking of axes,' said the Duchess, 'chop off her head!'

И, повернувшись к кухарке, прибавила: -- Возьми-ка ее в оборот! Для начала оттяпай ей голову!

Alice glanced rather anxiously at the cook, to see if she meant to take the hint; but the cook was busily stirring the soup, and seemed not to be listening, so she went on again: 'Twenty-four hours, I THINK; or is it twelve? I—'

Алиса с тревогой взглянула на кухарку, но та не обратила на этот намек никакого внимания и продолжала мешать свой суп. -- Кажется, за двадцать четыре,--продолжала задумчиво Алиса, -- а может, за двенадцать?

'Oh, don't bother ME,' said the Duchess; 'I never could abide figures!' And with that she began nursing her child again, singing a sort of lullaby to it as she did so, and giving it a violent shake at the end of every line:

-- Оставь меня в покое,--сказала Герцогиня.---С числами я никогда не ладила! Она запела колыбельную и принялась качать младенца, яростно встряхивая его в конце каждого куплета.

'Speak roughly to your little boy,

And beat him when he sneezes:

He only does it to annoy,

Because he knows it teases.'

Лупите своего сынка

За то, что он чихает

Он дразнит вас наверняка,

Нарочно раздражает!

CHORUS.

(In which the cook and the baby joined):—

'Wow! wow! wow!'

Припев:

(Его подхватили младенец и кухарка)

Гав! Гав! Гав!

While the Duchess sang the second verse of the song, she kept tossing the baby violently up and down, and the poor little thing howled so, that Alice could hardly hear the words:—

Герцогиня запела второй куплет. Она подбрасывала младенца к потолку и ловила его, а тот так визжал, что Алиса едва разбирала слова.

'I speak severely to my boy,

I beat him when he sneezes;

For he can thoroughly enjoy

The pepper when he pleases!'

Сынка любая лупит мать

За то, что он чихает.

Он мог бы перец обожать,

Да только не желает!

CHORUS.

'Wow! wow! wow!'

Припев:

Гав! Гав! Гав!

'Here! you may nurse it a bit, if you like!' the Duchess said to Alice, flinging the baby at her as she spoke. 'I must go and get ready to play croquet with the Queen,' and she hurried out of the room. The cook threw a frying-pan after her as she went out, but it just missed her.

-- Держи! -- крикнула вдруг Герцогиня и швырнула Алисе младенца. -- Можешь покачать его немного, если это тебе так нравится. А мне надо пойти и переодеться к крокету у Королевы. С этими словами она выбежала из кухни. Кухарка швырнула ей вдогонку кастрюлю, но промахнулась.

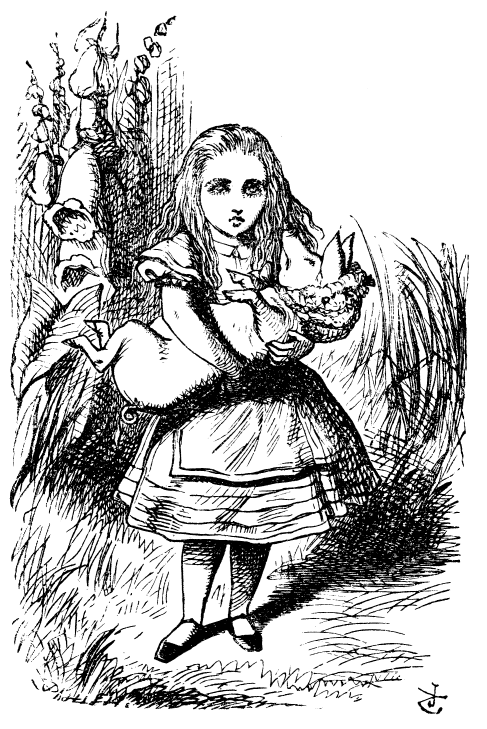

Alice caught the baby with some difficulty, as it was a queer-shaped little creature, and held out its arms and legs in all directions, 'just like a star-fish,' thought Alice. The poor little thing was snorting like a steam-engine when she caught it, and kept doubling itself up and straightening itself out again, so that altogether, for the first minute or two, it was as much as she could do to hold it.

Алиса чуть-чуть не выронила младенца из рук. Вид у него был какой-то странный, а руки и ноги торчали в разные стороны, как у морской звезды. Бедняжка пыхтел, словно паровоз, и весь изгибался так, что Алиса с трудом удерживала его.

As soon as she had made out the proper way of nursing it, (which was to twist it up into a sort of knot, and then keep tight hold of its right ear and left foot, so as to prevent its undoing itself,) she carried it out into the open air. 'IF I don't take this child away with me,' thought Alice, 'they're sure to kill it in a day or two: wouldn't it be murder to leave it behind?' She said the last words out loud, and the little thing grunted in reply (it had left off sneezing by this time). 'Don't grunt,' said Alice; 'that's not at all a proper way of expressing yourself.'

Наконец, она поняла, как надо с ним обращаться: взяла его одной рукой за правое ухо, а другой -- за левую ногу, скрутила в узел и держала, не выпуская ни на минуту. Так ей удалось вынести его из дома. -- Если я не возьму малыша с собой, -- подумала Алиса, -- они через денек-другой его прикончат. Оставить его здесь -- просто преступление! Последние слова она произнесла вслух, и младенец тихонько хрюкнул в знак согласия (чихать он уже перестал). -- Не хрюкай,--сказала Алиса.--Выражай свои мысли как-нибудь по-другому!

The baby grunted again, and Alice looked very anxiously into its face to see what was the matter with it. There could be no doubt that it had a VERY turn-up nose, much more like a snout than a real nose; also its eyes were getting extremely small for a baby: altogether Alice did not like the look of the thing at all. 'But perhaps it was only sobbing,' she thought, and looked into its eyes again, to see if there were any tears.

Младенец снова хрюкнул. Алиса с тревогой взглянула ему в лицо. Оно показалось ей очень подозрительным: нос такой вздернутый, что походил скорее на пятачок, а глаза для младенца слишком маленькие. В целом вид его Алисе совсем не понравился. -- Может, он просто всхлипнул, -- подумала она и посмотрела ему в глаза, нет ли там слез.

No, there were no tears. 'If you're going to turn into a pig, my dear,' said Alice, seriously, 'I'll have nothing more to do with you. Mind now!' The poor little thing sobbed again (or grunted, it was impossible to say which), and they went on for some while in silence.

Слез не было и в помине. -- Вот что, мой милый, -- сказала Алиса серьезно, -- если ты собираешься превратиться в поросенка, я с тобой больше знаться не стану. Так что смотри! Бедняжка снова всхлипнул (или всхрюкнул--трудно сказать!), и они продолжали свой путь в молчании.

Alice was just beginning to think to herself, 'Now, what am I to do with this creature when I get it home?' when it grunted again, so violently, that she looked down into its face in some alarm. This time there could be NO mistake about it: it was neither more nor less than a pig, and she felt that it would be quite absurd for her to carry it further.

Алиса уже начала подумывать о том, что с ним делать, когда она вернется домой, как вдруг он опять захрюкал, да так громко, что она перепуталась. Она вгляделась ему в лицо и ясно увидела: это был самый настоящий поросенок! Глупо было бы нести его дальше.

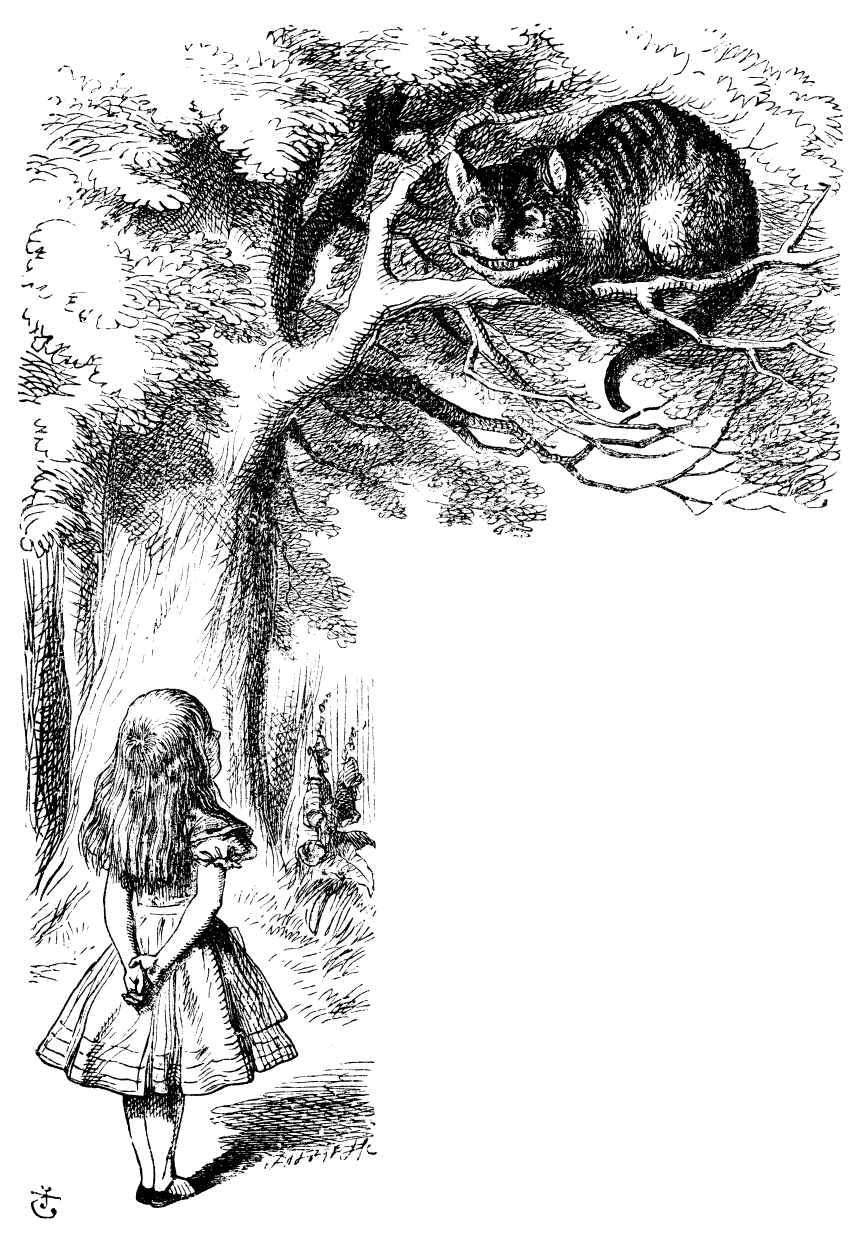

So she set the little creature down, and felt quite relieved to see it trot away quietly into the wood. 'If it had grown up,' she said to herself, 'it would have made a dreadfully ugly child: but it makes rather a handsome pig, I think.' And she began thinking over other children she knew, who might do very well as pigs, and was just saying to herself, 'if one only knew the right way to change them—' when she was a little startled by seeing the Cheshire Cat sitting on a bough of a tree a few yards off.

Алиса пустила его на землю и очень обрадовалась, увидев, как весело он затрусил прочь. -- Если б он немного подрос, -- подумала она, -- из него бы вышел весьма неприятный ребенок. А как поросенок он очень мил! И она принялась вспоминать других детей, из которых вышли бы отличные поросята. -- Знать бы только, как их превращать, -- подумала она и вздрогнула. В нескольких шагах от нее на ветке сидел Чеширский Кот.

The Cat only grinned when it saw Alice. It looked good-natured, she thought: still it had VERY long claws and a great many teeth, so she felt that it ought to be treated with respect.

Завидев Алису, Кот только улыбнулся. Вид у него был добродушный, но когти длинные, а зубов так много, что Алиса сразу поняла, что с ним шутки плохи.

'Cheshire Puss,' she began, rather timidly, as she did not at all know whether it would like the name: however, it only grinned a little wider. 'Come, it's pleased so far,' thought Alice, and she went on. 'Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?'

-- Котик! Чешик! -- робко начала Алиса. Она не знала, понравится ли ему это имя, но он только шире улыбнулся в ответ. -- Ничего, -- подумала Алиса, -- кажется, доволен. Вслух же она спросила: -- Скажите, пожалуйста, куда мне отсюда идти?

'That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,' said the Cat.

-- А куда ты хочешь попасть? -- ответил Кот.

'I don't much care where—' said Alice.

-- Мне все равно... -- сказала Алиса.

'Then it doesn't matter which way you go,' said the Cat.

-- Тогда все равно, куда и идти, -- заметил Кот.

'—so long as I get SOMEWHERE,' Alice added as an explanation.

-- ...только бы попасть куда-нибудь, -- пояснила Алиса.

'Oh, you're sure to do that,' said the Cat, 'if you only walk long enough.'

-- Куда-нибудь ты обязательно попадешь, -- сказал Кот. -- Нужно только достаточно долго идти.

Alice felt that this could not be denied, so she tried another question. 'What sort of people live about here?'

С этим нельзя было не согласиться. Алиса решила переменить тему. -- А что здесь за люди живут? -- спросила она.

'In THAT direction,' the Cat said, waving its right paw round, 'lives a Hatter: and in THAT direction,' waving the other paw, 'lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they're both mad.'

-- Вон там,--сказал Кот и махнул правой лапой,--живет Болванщик. А там,--и он махнул левой,--Мартовский Заяц. Все равно, к кому ты пойдешь. Оба не в своем уме.

'But I don't want to go among mad people,' Alice remarked.

-- На что мне безумцы? -- сказала Алиса.

'Oh, you can't help that,' said the Cat: 'we're all mad here. I'm mad. You're mad.'

-- Ничего не поделаешь, -- возразил Кот. -- Все мы здесь не в своем уме -- и ты, и я.

'How do you know I'm mad?' said Alice.

-- Откуда вы знаете, что я не в своем уме? -- спросила Алиса.

'You must be,' said the Cat, 'or you wouldn't have come here.'

-- Конечно, не в своем,--ответил Кот.--Иначе как бы ты здесь оказалась?

Alice didn't think that proved it at all; however, she went on 'And how do you know that you're mad?'

Довод этот показался Алисе совсем не убедительным, но она не стала спорить, а только спросила: -- А откуда вы знаете, что вы не в своем уме?

'To begin with,' said the Cat, 'a dog's not mad. You grant that?'

-- Начнем с того, что пес в своем уме. Согласна?

'I suppose so,' said Alice.

-- Допустим, -- согласилась Алиса.

'Well, then,' the Cat went on, 'you see, a dog growls when it's angry, and wags its tail when it's pleased. Now I growl when I'm pleased, and wag my tail when I'm angry. Therefore I'm mad.'

-- Дальше, -- сказал Кот. -- Пес ворчит, когда сердится, а когда доволен, виляет хвостом. Ну, а я ворчу, когда я доволен, и виляю хвостом, когда сержусь. Следовательно, я не в своем уме.

'I call it purring, not growling,' said Alice.

-- По-моему, вы не ворчите, а мурлыкаете,--возразила Алиса. -- Во всяком случае, я это так называю.

'Call it what you like,' said the Cat. 'Do you play croquet with the Queen to-day?'

-- Называй как хочешь, -- ответил Кот. -- Суть от этого не меняется. Ты играешь сегодня в крокет у Королевы?

'I should like it very much,' said Alice, 'but I haven't been invited yet.'

-- Мне бы очень хотелось, -- сказала Алиса, -- но меня еще не пригласили.

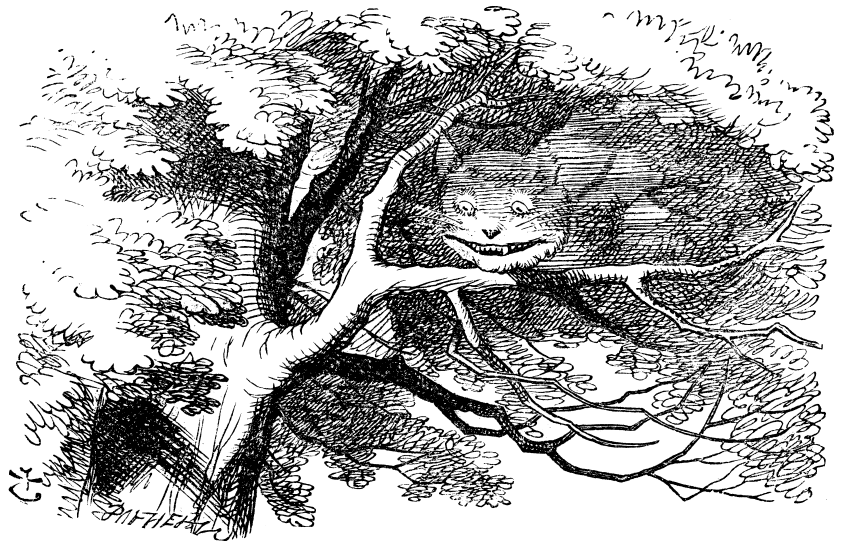

'You'll see me there,' said the Cat, and vanished.

-- Тогда до вечера, -- сказал Кот и исчез.

Alice was not much surprised at this, she was getting so used to queer things happening. While she was looking at the place where it had been, it suddenly appeared again.

Алиса не очень этому удивилась -- она уже начала привыкать ко всяким странностям. Она стояла и смотрела на ветку, где только что сидел Кот, как вдруг он снова возник на том же месте.

'By-the-bye, what became of the baby?' said the Cat. 'I'd nearly forgotten to ask.'

-- Кстати, что сталось с ребенком?--сказал Кот.--Совсем забыл тебя спросить.

'It turned into a pig,' Alice quietly said, just as if it had come back in a natural way.

-- Он превратился в поросенка, -- отвечала Алиса, и глазом не моргнув.

'I thought it would,' said the Cat, and vanished again.

-- Я так и думал, -- сказал Кот и снова исчез.

Alice waited a little, half expecting to see it again, but it did not appear, and after a minute or two she walked on in the direction in which the March Hare was said to live. 'I've seen hatters before,' she said to herself; 'the March Hare will be much the most interesting, and perhaps as this is May it won't be raving mad—at least not so mad as it was in March.' As she said this, she looked up, and there was the Cat again, sitting on a branch of a tree.

Алиса подождала немного, не появится ли он опять, но он не появлялся, и она пошла туда, где, по его словам, жил Мартовский Заяц. -- Шляпных дел мастеров я уже видела, -- говорила она про себя. -- Мартовский Заяц, по-моему, куда интереснее. К тому же сейчас май -- возможно, он уже немножко пришел в себя. Тут она подняла глаза и снова увидела Кота.

'Did you say pig, or fig?' said the Cat.

-- Как ты сказала: в поросенка или гусенка? -- спросил Кот.

'I said pig,' replied Alice; 'and I wish you wouldn't keep appearing and vanishing so suddenly: you make one quite giddy.'

-- Я сказала: в поросенка, -- ответила Алиса. -- А вы можете исчезать и появляться не так внезапно? А то у меня голова идет кругом.

'All right,' said the Cat; and this time it vanished quite slowly, beginning with the end of the tail, and ending with the grin, which remained some time after the rest of it had gone.

-- Хорошо, -- сказал Кот и исчез -- на этот раз очень медленно. Первым исчез кончик его хвоста, а последней -- улыбка; она долго парила в воздухе, когда все остальное уже пропало.

'Well! I've often seen a cat without a grin,' thought Alice; 'but a grin without a cat! It's the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!'

-- Д-да! -- подумала Алиса. -- Видала я котов без улыбки, но улыбки без кота! Такого я в жизни еще не встречала.

She had not gone much farther before she came in sight of the house of the March Hare: she thought it must be the right house, because the chimneys were shaped like ears and the roof was thatched with fur. It was so large a house, that she did not like to go nearer till she had nibbled some more of the lefthand bit of mushroom, and raised herself to about two feet high: even then she walked up towards it rather timidly, saying to herself 'Suppose it should be raving mad after all! I almost wish I'd gone to see the Hatter instead!'

Пройдя немного дальше, она увидела домик Мартовского Зайца. Ошибиться было невозможно -- на крыше из заячьего меха торчали две трубы, удивительно похожие на заячьи уши. Дом был такой большой, что Алиса решила сначала съесть немного гриба, который она держала в левой руке. Подождав, пока не вырастет до двух футов, она неуверенно двинулась к дому. -- А вдруг он все-таки буйный? -- думала она. -- Пошла бы я лучше к Болванщику!

Audio from LibreVox.org