Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

CHAPTER VII.

VII

A Mad Tea-Party

Een dolle theevisite

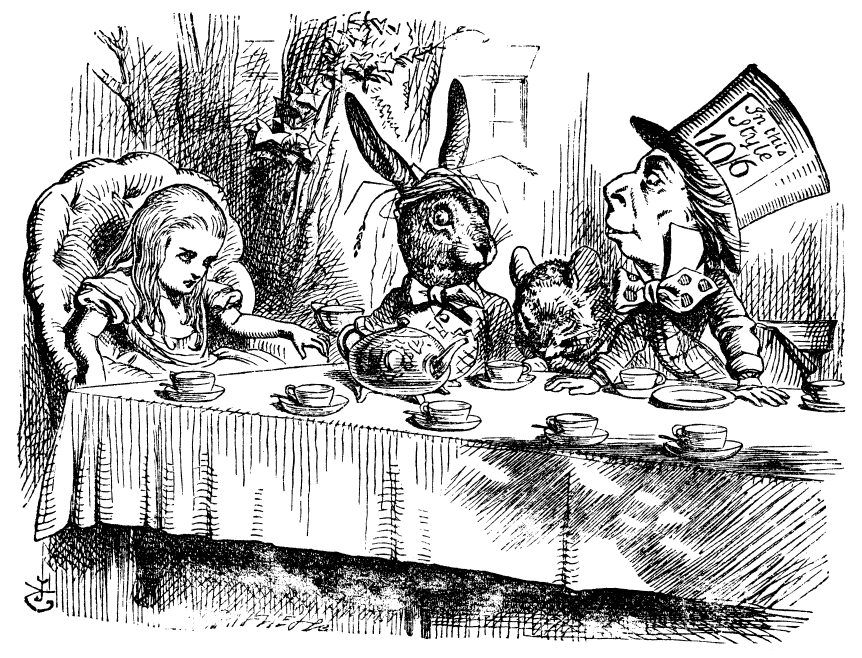

There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head. 'Very uncomfortable for the Dormouse,' thought Alice; 'only, as it's asleep, I suppose it doesn't mind.'

ER stond een tafel onder een boom tegenover het huis en daaraan zaten de Maartse Haas en de Hoedenmaker thee te drinken; een Zevenslaper zat vast in slaap tussen hen in en de twee anderen gebruikten hem als kussen, leunden met hun ellebogen op hem en praatten over zijn hoofd heen. ‘Erg ongemakkelijk voor de Zevenslaper,’ dacht Alice, ‘alleen, nu hij slaapt, komt het er niet veel op aan ook.’

The table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it: 'No room! No room!' they cried out when they saw Alice coming. 'There's PLENTY of room!' said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in a large arm-chair at one end of the table.

De tafel was heel groot, maar de drie thee-drinkers zaten op elkaar gedrongen aan een hoekje. ‘Geen plaats, geen plaats!’ riepen zij, toen zij Alice aan zagen komen. ‘Er is plaats genoeg!’ zei Alice verontwaardigd en zij ging in een grote leunstoel zitten aan het ene eind van de tafel.

'Have some wine,' the March Hare said in an encouraging tone.

‘Neem wat wijn,’ zei de Maartse Haas aanmoedigend.

Alice looked all round the table, but there was nothing on it but tea. 'I don't see any wine,' she remarked.

Alice keek de hele tafel rond, maar zager enkel thee op staan - ‘Ik zie helemaal geen wijn,’ merkte ze op.

'There isn't any,' said the March Hare.

‘Die is er ook niet,’ zei de Maartse Haas.

'Then it wasn't very civil of you to offer it,' said Alice angrily.

‘Dan was het niet erg beleefd van je om die aan te bieden,’ zei Alice boos.

'It wasn't very civil of you to sit down without being invited,' said the March Hare.

‘Het was niet erg beleefd van jou om zo maar te gaan zitten,’ zei de Maartse Haas.

'I didn't know it was YOUR table,' said Alice; 'it's laid for a great many more than three.'

‘Ik wist niet dat het uw tafel was,’ zei Alice, ‘hij is voor veel meer dan drie mensen gedekt.’

'Your hair wants cutting,' said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech.

‘Je haar moet geknipt worden,’ zei de Hoedenmaker. Hij had Alice een hele tijd nieuwsgierig op zitten nemen en dit was het eerste wat hij zei.

'You should learn not to make personal remarks,' Alice said with some severity; 'it's very rude.'

‘U moet niet zo persoonlijk worden,’ zei Alice streng, ‘dat is erg grof.’

The Hatter opened his eyes very wide on hearing this; but all he SAID was, 'Why is a raven like a writing-desk?'

De Hoedenmaker deed zijn ogen wijd open toen hij dit hoorde; toen zei hij enkel: ‘Waarom lijkt een raaf op een schrijftafel?’

'Come, we shall have some fun now!' thought Alice. 'I'm glad they've begun asking riddles.—I believe I can guess that,' she added aloud.

‘Kom, nu zal het leuk worden,’ dacht Alice, ‘ik ben blij dat ze raadsels op gaan geven. Ik geloof wel dat ik dat kan raden.’ voegde ze er hardop aan toe.

'Do you mean that you think you can find out the answer to it?' said the March Hare.

‘Bedoel je, dat je denkt dat je het antwoord erop kan vinden?’ zei de Maartse Haas.

'Exactly so,' said Alice.

‘Ja,’ zei Alice.

'Then you should say what you mean,' the March Hare went on.

‘Dan moet je zeggen wat je bedoelt,’ antwoordde de Maartse Haas.

'I do,' Alice hastily replied; 'at least—at least I mean what I say—that's the same thing, you know.'

‘Dat doe ik,’ antwoorde Alice haastig, ‘tenminste ik bedoel wat ik zeg - dat is hetzelfde, ziet u.’

'Not the same thing a bit!' said the Hatter. 'You might just as well say that "I see what I eat" is the same thing as "I eat what I see"!'

‘Dat is helemaal niet hetzelfde,’ zei de Hoedenmaker, ‘je kunt even goed zeggen dat “ik zie wat ik eet” hetzelfde is als “ik eet wat ik zie”!’

'You might just as well say,' added the March Hare, 'that "I like what I get" is the same thing as "I get what I like"!'

‘Dan kun je even goed zeggen,’ voegde de Maartse Haas er aan toe, ‘dat “ik houd van wat ik krijg” hetzelfde is als “ik krijg waarvan ik houd”!’

'You might just as well say,' added the Dormouse, who seemed to be talking in his sleep, 'that "I breathe when I sleep" is the same thing as "I sleep when I breathe"!'

‘Dan kun je evengoed zeggen,’ zei de Zevenslaper, die blijkbaar in zijn slaap praatte, ‘dat “ik adem als ik slaap,” hetzelfde is als “ik slaap als ik adem”!’

'It IS the same thing with you,' said the Hatter, and here the conversation dropped, and the party sat silent for a minute, while Alice thought over all she could remember about ravens and writing-desks, which wasn't much.

‘Dat is hetzelfde bij jou,’ zei de Hoedenmaker en hier brak het gesprek af en zweeg het gezelschap een paar minuten, terwijl Alice over alles nadacht, wat haar over raven en schrijftafels te binnen wou schieten en dat was niet veel.

The Hatter was the first to break the silence. 'What day of the month is it?' he said, turning to Alice: he had taken his watch out of his pocket, and was looking at it uneasily, shaking it every now and then, and holding it to his ear.

De Hoedenmaker was de eerste die weer begon te praten. ‘De hoeveelste is het?’ zei hij en wendde zich tot Alice; hij had zijn horloge uit zijn zak gehaald en keek er nijdig naar, schudde het zo nu en dan en hield het dan aan zijn oor.

Alice considered a little, and then said 'The fourth.'

Alice dacht even na en zei toen ‘De vierde.’

'Two days wrong!' sighed the Hatter. 'I told you butter wouldn't suit the works!' he added looking angrily at the March Hare.

‘Twee dagen achter,’ zuchtte de Hoedenmaker, ‘ik heb je wel gezegd dat boter niet goed voor het uurwerk is,’ voegde hij er aan toe en keek de Maartse Haas boos aan.

'It was the BEST butter,' the March Hare meekly replied.

‘Het was toch beste boter,’ antwoordde de Maartse Haas deemoedig.

'Yes, but some crumbs must have got in as well,' the Hatter grumbled: 'you shouldn't have put it in with the bread-knife.'

‘Maar er zaten vast broodkruimels in,’ mopperde de Hoedenmaker, ‘je had de boter er ook niet met het broodmes in moeten stoppen.’

The March Hare took the watch and looked at it gloomily: then he dipped it into his cup of tea, and looked at it again: but he could think of nothing better to say than his first remark, 'It was the BEST butter, you know.'

De Maartse Haas nam het horloge weer op en keek er somber naar; toen stopte hij het in zijn kop thee en keek er weer naar, maar hij kon niets beters bedenken dan zijn vroegere opmerking: ‘Het was toch beste boter.’

Alice had been looking over his shoulder with some curiosity. 'What a funny watch!' she remarked. 'It tells the day of the month, and doesn't tell what o'clock it is!'

Alice had nieuwsgierig over zijn schouder gekeken. ‘Wat een grappig horloge!’ zei ze, ‘je kunt er op zien welke dag het is en niet eens hoe laat het is.’

'Why should it?' muttered the Hatter. 'Does YOUR watch tell you what year it is?'

‘En wat dan nog?’ mompelde de Hoedenmaker, ‘kan je op jouw horloge zien welk jaar het is?’

'Of course not,' Alice replied very readily: 'but that's because it stays the same year for such a long time together.'

‘Natuurlijk niet,’ antwoordde Alice, ‘maar dat is omdat het zolang hetzelfde jaar blijft.’

'Which is just the case with MINE,' said the Hatter.

‘Precies zoals met het mijne,’ zei de Hoedenmaker.

Alice felt dreadfully puzzled. The Hatter's remark seemed to have no sort of meaning in it, and yet it was certainly English. 'I don't quite understand you,' she said, as politely as she could.

Hier begreep Alice niets van. Wat de Hoedenmaker zei, scheen volkomen onzin en toch was het goed Nederlands. ‘Dat begrijp ik niet helemaal,’ zei ze zo beleefd als ze kon.

'The Dormouse is asleep again,' said the Hatter, and he poured a little hot tea upon its nose.

‘De Zevenslaper slaapt weer,’ zei de Hoedenmaker en hij goot hem een beetje hete thee op zijn neus.

The Dormouse shook its head impatiently, and said, without opening its eyes, 'Of course, of course; just what I was going to remark myself.'

De Zevenslaper schudde ongeduldig zijn hoofd en zei zonder zijn ogen op te slaan: ‘Natuurlijk, natuurlijk, dat wou ik juist zeggen.’

'Have you guessed the riddle yet?' the Hatter said, turning to Alice again.

‘Heb je het raadsel al opgelost?’ zei de Hoedenmaker en wendde zich weer tot Alice.

'No, I give it up,' Alice replied: 'what's the answer?'

‘Nee, ik geef het op,’ antwoordde Alice, ‘wat is de oplossing?’

'I haven't the slightest idea,' said the Hatter.

‘Ik heb er geen flauw idee van,’ zei de Hoedenmaker.

'Nor I,' said the March Hare.

‘Ik evenmin,’ zei de Maartse Haas.

Alice sighed wearily. 'I think you might do something better with the time,' she said, 'than waste it in asking riddles that have no answers.'

Alice moest er van zuchten. ‘Je kunt je tijd toch wel beter besteden,’ zei ze, ‘dan haar met raadsels te verknoeien, waar geen antwoord op is.’

'If you knew Time as well as I do,' said the Hatter, 'you wouldn't talk about wasting IT. It's HIM.'

‘Als je de Tijd even goed kende als ik,’ zei de Hoedenmaker, ‘zou je niet over haar praten. Het is hem.’

'I don't know what you mean,' said Alice.

‘Ik begrijp niet wat u bedoelt,’ zei Alice.

'Of course you don't!' the Hatter said, tossing his head contemptuously. 'I dare say you never even spoke to Time!'

‘Natuurlijk niet!’ zei de Hoedenmaker en schudde minachtend zijn hoofd, ‘ik wed dat jij nooit met de Tijd hebt gepraat.’

'Perhaps not,' Alice cautiously replied: 'but I know I have to beat time when I learn music.'

‘Misschien niet,’ antwoordde Alice voorzichtig, ‘maar ik moet altijd erg op de tijd passen als ik piano studeer.’

'Ah! that accounts for it,' said the Hatter. 'He won't stand beating. Now, if you only kept on good terms with him, he'd do almost anything you liked with the clock. For instance, suppose it were nine o'clock in the morning, just time to begin lessons: you'd only have to whisper a hint to Time, and round goes the clock in a twinkling! Half-past one, time for dinner!'

‘Daar heb je het!’ zei de Hoedenmaker, ‘hij houdt er niet van als er op hem gepast wordt. Nee, als je maar zorgt, dat je op goede voet met hem staat, doet hij alles wat je wilt met de klok. Bijvoorbeeld, als het negen uur is en de school begint, dan hoef je de Tijd maar even iets in zijn oor te fluisteren en in een oogopslag is het twaalf uur: etenstijd!’

('I only wish it was,' the March Hare said to itself in a whisper.)

(‘Ik wou dat het waar was,’ fluisterde de Maartse Haas bij zichzelf).

'That would be grand, certainly,' said Alice thoughtfully: 'but then—I shouldn't be hungry for it, you know.'

‘Dat zou prachtig zijn,’ zei Alice, ‘maar dan zou ik nog geen honger hebben.’

'Not at first, perhaps,' said the Hatter: 'but you could keep it to half-past one as long as you liked.'

‘Eerst niet,’ zei de Hoedenmaker, ‘maar je kunt het net zo lang twaalf uur laten blijven als je wilt.’

'Is that the way YOU manage?' Alice asked.

‘Doet u dat dan ook zo?’ vroeg Alice.

The Hatter shook his head mournfully. 'Not I!' he replied. 'We quarrelled last March—just before HE went mad, you know—' (pointing with his tea spoon at the March Hare,) '—it was at the great concert given by the Queen of Hearts, and I had to sing

De Hoedenmaker schudde treurig het hoofd. ‘Helaas,’ antwoordde hij, ‘we hebben in Maart - net voor hij gek werd - (hier wees hij met zijn theelepeltje naar de Maartse Haas) ruzie gekregen. Het was op het grote concert dat de Hartenkoningin gaf en ik moest zingen:

"Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!

How I wonder what you're at!"

Knipoog vleermuis, knipoog zoet,

Zeg mij toch wat of gij doet.

You know the song, perhaps?'

‘Ken je dat liedje?’

'I've heard something like it,' said Alice.

‘Ik heb wel eens zo iets gehoord,’ zei Alice.

'It goes on, you know,' the Hatter continued, 'in this way:—

‘Zo gaat het verder,’ vervolgde de Hoedenmaker:

"Up above the world you fly,

Like a tea-tray in the sky.

Twinkle, twinkle—"'

Boven d' aarde scheert uw vlucht Als een theeblad door de lucht.

Knipoog Vleermuis -

Here the Dormouse shook itself, and began singing in its sleep 'Twinkle, twinkle, twinkle, twinkle—' and went on so long that they had to pinch it to make it stop.

Hier kwam er wat beweging in de Zevenslaper en hij begon in zijn slaap te zingen ‘Knipoog, knipoog, knipoog, knipoog, knipoog’ en ging daar zo lang mee door dat ze hem knijpen moesten om hem weer stil te krijgen.

'Well, I'd hardly finished the first verse,' said the Hatter, 'when the Queen jumped up and bawled out, "He's murdering the time! Off with his head!"'

‘Ik had amper het eerste couplet gezongen,’ zei de Hoedenmaker, ‘toen de Koningin opsprong en schreeuwde ‘Hij is de Tijd aan het doden. Sla zijn hoofd af!’

'How dreadfully savage!' exclaimed Alice.

‘Wat afschuwelijk wreed,’ riep Alice uit.

'And ever since that,' the Hatter went on in a mournful tone, 'he won't do a thing I ask! It's always six o'clock now.'

‘En sindsdien,’ ging de Hoedenmaker treurig verder, ‘doet hij nooit meer wat ik vraag. Het is nu altijd vier uur.’

A bright idea came into Alice's head. 'Is that the reason so many tea-things are put out here?' she asked.

Nu ging Alice een licht op. ‘Staat daarom al die theeboel op tafel?’ vroeg ze.

'Yes, that's it,' said the Hatter with a sigh: 'it's always tea-time, and we've no time to wash the things between whiles.'

‘Ja, zo is het,’ zei de Hoedenmaker met een zucht, ‘het is altijd theetijd en we hebben geen tijd om de vaten onderwijl om te wassen.’

'Then you keep moving round, I suppose?' said Alice.

‘Dan schuiven jullie dus steeds op,’ zei Alice.

'Exactly so,' said the Hatter: 'as the things get used up.'

‘Precies,’ zei de Hoedenmaker, ‘wanneer de boel te vuil wordt.’

'But what happens when you come to the beginning again?' Alice ventured to ask.

‘En wat doen jullie dan als je weer aan het begin gekomen bent?’ waagde Alice te vragen.

'Suppose we change the subject,' the March Hare interrupted, yawning. 'I'm getting tired of this. I vote the young lady tells us a story.'

‘Laten we over wat anders gaan praten,’ zei de Maartse Haas geeuwend, ‘ik heb hier genoeg van. Ik vind dat de jonge dame ons wel een verhaal kan vertellen.

'I'm afraid I don't know one,' said Alice, rather alarmed at the proposal.

‘Ik weet er geen’ zei Alice, die schrok van dit voorstel.

'Then the Dormouse shall!' they both cried. 'Wake up, Dormouse!' And they pinched it on both sides at once.

‘Dan moet de Zevenslaper het doen!’ riepen zij beiden uit, ‘Zevenslaper, word wakker!’ En zij knepen hem plotseling ieder in een zij.

The Dormouse slowly opened his eyes. 'I wasn't asleep,' he said in a hoarse, feeble voice: 'I heard every word you fellows were saying.'

De Zevenslaper deed langzaam zijn ogen open. ‘Ik sliep niet,’ zei hij met een hese en zwakke stem, ‘ik heb ieder woord gehoord, dat jullie zeiden.’

'Tell us a story!' said the March Hare.

‘Vertel ons een verhaal,’ zei de Maartse Haas.

'Yes, please do!' pleaded Alice.

‘Ja als-t-u-blieft,’ smeekte Alice.

'And be quick about it,' added the Hatter, 'or you'll be asleep again before it's done.'

‘En begin een beetje gauw,’ voegde de Hoedenmaker er aan toe, ‘want anders slaap je weer in.’

'Once upon a time there were three little sisters,' the Dormouse began in a great hurry; 'and their names were Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie; and they lived at the bottom of a well—'

‘Er waren eens drie zusjes,’ begon de Zevenslaper haastig, ‘en zij heetten Trinie, Minie en Linie en zij woonden op de bodem van een put -’

'What did they live on?' said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions of eating and drinking.

‘Waar leefden ze van?’ vroeg Alice, die het altijd erg interessant vond wat mensen aten en dronken.

'They lived on treacle,' said the Dormouse, after thinking a minute or two.

‘Van stroop,’ zei de Zevenslaper na een ogenblikje te hebben nagedacht.

'They couldn't have done that, you know,' Alice gently remarked; 'they'd have been ill.'

‘Dat kan toch nooit,’ merkte Alice vriendelijk op, ‘dan zouden ze toch ziek worden.’

'So they were,' said the Dormouse; 'VERY ill.'

‘Dat waren ze ook,’ zei de Zevenslaper, ‘erg ziek.’

Alice tried to fancy to herself what such an extraordinary ways of living would be like, but it puzzled her too much, so she went on: 'But why did they live at the bottom of a well?'

Alice trachtte zich die buitengewone manier van leven voor te stellen, maar zij vond het wel een erg moeilijk probleem en daarom ging ze verder: ‘Maar waarom leefden ze op de bodem van een put?’

'Take some more tea,' the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly.

‘Neem gerust wat meer thee,’ zei de Maartse Haas heel ernstig tot Alice.

'I've had nothing yet,' Alice replied in an offended tone, 'so I can't take more.'

‘Ik heb nog niets gehad,’ zei Alice boos, ‘dus kan ik onmogelijk meer nemen.’

'You mean you can't take LESS,' said the Hatter: 'it's very easy to take MORE than nothing.'

‘Je bedoelt dat je niet minder kunt nemen,’ zei de Hoedenmaker, ‘het is heel gemakkelijk om meer te nemen dan niets.’

'Nobody asked YOUR opinion,' said Alice.

‘Niemand heeft jou iets gevraagd,’ zei Alice.

'Who's making personal remarks now?' the Hatter asked triumphantly.

‘En wie is er nu persoonlijk?’ vroeg de Hoedenmaker triomfantelijk.

Alice did not quite know what to say to this: so she helped herself to some tea and bread-and-butter, and then turned to the Dormouse, and repeated her question. 'Why did they live at the bottom of a well?'

Alice wist hierop niets te zeggen; daarom schonk ze zichzelf wat thee in, nam een boterham met boter, wendde zich tot de Zevenslaper en herhaalde haar vraag: ‘waarom woonden ze op de bodem van een put?’

The Dormouse again took a minute or two to think about it, and then said, 'It was a treacle-well.'

De Zevenslaper dacht weer een poosje na en zei toen: ‘Het was een stroopput.’

'There's no such thing!' Alice was beginning very angrily, but the Hatter and the March Hare went 'Sh! sh!' and the Dormouse sulkily remarked, 'If you can't be civil, you'd better finish the story for yourself.'

‘Er bestaan geen stroopputten’ begon Alice erg boos, maar de Hoedenmaker en de Maartse Haas riepen: ‘St, st’ en de Zevenslaper merkte knorrig op: ‘Als je je niet behoorlijk gedragen kunt, kun je het verhaal beter zelf afmaken.’

'No, please go on!' Alice said very humbly; 'I won't interrupt again. I dare say there may be ONE.'

‘Nee, gaat u alstublieft verder,’ zei Alice, ‘ik zal u niet meer onderbreken. Het kan eigenlijk best waar zijn.’

'One, indeed!' said the Dormouse indignantly. However, he consented to go on. 'And so these three little sisters—they were learning to draw, you know—'

‘Natuurlijk kan het,’ zei de Zevenslaper verontwaardigd. En hij vertelde verder: ‘En die drie zusjes, die leerden scheppend werk, weet je.’

'What did they draw?' said Alice, quite forgetting her promise.

‘Wat voor scheppend werk?’ vroeg Alice, die haar belofte weer vergeten had.

'Treacle,' said the Dormouse, without considering at all this time.

‘Stroop scheppen,’ zei de Zevenslaper, zonder na te denken dit keer.

'I want a clean cup,' interrupted the Hatter: 'let's all move one place on.'

‘Ik moet een schoon bordje hebben,’ onderbrak de Hoedenmaker, ‘laten we een plaats opschuiven.’

He moved on as he spoke, and the Dormouse followed him: the March Hare moved into the Dormouse's place, and Alice rather unwillingly took the place of the March Hare. The Hatter was the only one who got any advantage from the change: and Alice was a good deal worse off than before, as the March Hare had just upset the milk-jug into his plate.

Hij stond op terwijl hij dit zei en de Zevenslaper nam zijn plaats in; de Maartse Haas ging op de stoel van de Zevenslaper zitten en Alice nogal tegen haar zin op die van de Maartse Haas. De Hoedenmaker was de enige, die enig voordeel had van deze verandering en Alice was er nu heel wat slechter aan toe, want de Maartse Haas had net de melkkan over zijn bord omgegooid.

Alice did not wish to offend the Dormouse again, so she began very cautiously: 'But I don't understand. Where did they draw the treacle from?'

Alice wilde de Zevenslaper niet opnieuw ergeren en daarom vroeg zij heel voorzichtig: ‘Maar ik begrijp het niet goed. Waar schepten zij die stroop dan uit?’

'You can draw water out of a water-well,' said the Hatter; 'so I should think you could draw treacle out of a treacle-well—eh, stupid?'

‘Je kan water scheppen uit een waterput,’ zei de Hoedenmaker; ‘dan kan je volgens mij stroopscheppen uit een stroopput, is het niet, Domoor?’

'But they were IN the well,' Alice said to the Dormouse, not choosing to notice this last remark.

‘Maar ze waren in die put,’ zei Alice tegen de Zevenslaper zonder veel acht te slaan op deze opmerking.

'Of course they were', said the Dormouse; '—well in.'

‘Zeker,’ zei de Zevenslaper, ‘inderdaad, heel diep er in.’

This answer so confused poor Alice, that she let the Dormouse go on for some time without interrupting it.

Dit antwoord verbaasde de arme Alice zo, dat zij de Zevenslaper een poosje door liet vertellen zonder hem in de rede te vallen.

'They were learning to draw,' the Dormouse went on, yawning and rubbing its eyes, for it was getting very sleepy; 'and they drew all manner of things—everything that begins with an M—'

‘Zij leerden dus scheppen,’ ging de Zevenslaper verder, terwijl hij alsmaar geeuwde en in zijn ogen wreef van slaap, ‘en ze schiepen een heleboel dingen, alles wat met een B begint.’

'Why with an M?' said Alice.

‘Waarom met een B?’ zei Alice.

'Why not?' said the March Hare.

‘Waarom niet?’ zei de Maartse Haas.

Alice was silent.

Alice zweeg.

The Dormouse had closed its eyes by this time, and was going off into a doze; but, on being pinched by the Hatter, it woke up again with a little shriek, and went on: '—that begins with an M, such as mouse-traps, and the moon, and memory, and muchness—you know you say things are "much of a muchness"—did you ever see such a thing as a drawing of a muchness?'

De Zevenslaper had zijn ogen gesloten en ging langzamerhand onder zeil, maar toen de Hoedenmaker hem kneep, werd hij met een gilletje wakker en ging verder: ‘Alles wat begint met een B, bijvoorbeeld bakblikken, beenbreuken, brandingen en behagen; - je hebt natuurlijk wel eens horen zeggen: ‘hij schept er behagen in’, maar heb je dat ooit iemand er uitzien scheppen!’

'Really, now you ask me,' said Alice, very much confused, 'I don't think—'

‘Nee, nu u het vraagt,’ zei Alice verbaasd, ‘ik denk niet...’

'Then you shouldn't talk,' said the Hatter.

‘Dan moet je ook niets zeggen,’ zei de Hoedenmaker.

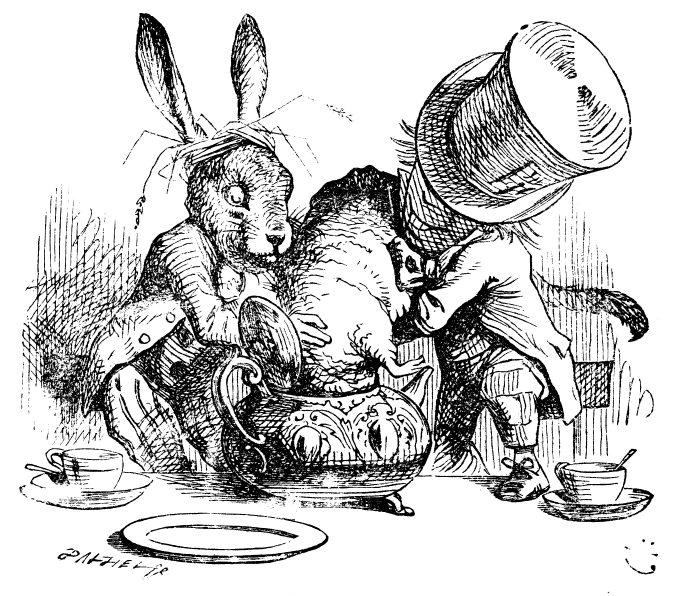

This piece of rudeness was more than Alice could bear: she got up in great disgust, and walked off; the Dormouse fell asleep instantly, and neither of the others took the least notice of her going, though she looked back once or twice, half hoping that they would call after her: the last time she saw them, they were trying to put the Dormouse into the teapot.

Deze grofheid was Alice toch te bar; zij stond verontwaardigd op en wandelde weg; de Zevenslaper viel op hetzelfde ogenblik in slaap en niemand van de anderen scheen notitie te nemen van haar vertrek; toch keek zij nog een paar keer om, half in de hoop dat zij haar terug zouden roepen. Het laatste wat zij zag, was, dat zij probeerden de Zevenslaper in de theepot te stoppen.

'At any rate I'll never go THERE again!' said Alice as she picked her way through the wood. 'It's the stupidest tea-party I ever was at in all my life!'

‘In elk geval ga ik daar nooit meer naar toe,’ zei Alice, toen zij haar wandeling door het hos voortzette, ‘dit was de malste theevisite, die ik in mijn leven mee gemaakt heb.’

Just as she said this, she noticed that one of the trees had a door leading right into it. 'That's very curious!' she thought. 'But everything's curious today. I think I may as well go in at once.' And in she went.

Juist toen zij dit zei, zag zij in één van de bomen een deur. ‘Dat is wel heel gek,’ dacht ze, ‘maar tenslotte is vandaag alles even gek. Ik vind dat ik best eens naar binnen kan gaan.’ En zij ging naar binnen.

Once more she found herself in the long hall, and close to the little glass table. 'Now, I'll manage better this time,' she said to herself, and began by taking the little golden key, and unlocking the door that led into the garden. Then she went to work nibbling at the mushroom (she had kept a piece of it in her pocket) till she was about a foot high: then she walked down the little passage: and THEN—she found herself at last in the beautiful garden, among the bright flower-beds and the cool fountains.

Ze kwam weer in de lange zaal, dicht bij het glazen tafeltje. ‘Nu zal ik beter oppassen,’ zei ze bij zichzelf en nam eerst het sleuteltje van de tafel en deed daarmee de deur naar de tuin open. Toen knabbelde ze weer wat aan de paddestoel (ze had een stuk in haar zak gestopt) tot zij nog dertig centimeter groot was en liep door de smalle gang en toen - toen kwam zij eindelijk in de mooie tuin met de kleurige bloemenbedden en de koele fonteinen.

Audio from LibreVox.org