Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

CHAPTER XII.

XII

Alice's Evidence

La testimonianza di Alice

'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before.

— Presente! — rispose Alice.

Dimenticando, nella confusione di quell’istante di esser cresciuta enormemente, saltò con tanta fretta che rovesciò col lembo della veste il banco de’ giurati, i quali capitombolarono con la testa in giù sulla folla, restando con le. gambe in aria. Questo le rammentò l’urtone dato la settimana prima a un globo di cristallo con i pesciolini d’oro.

'Oh, I BEG your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die.

— Oh, vi prego di scusarmi! — ella esclamò con voce angosciata e cominciò a raccoglierli con molta sollecitudine, perchè invasa dall’idea dei pesciolini pensava di doverli prontamente raccogliere e rimettere sul loro banco se non li voleva far morire.

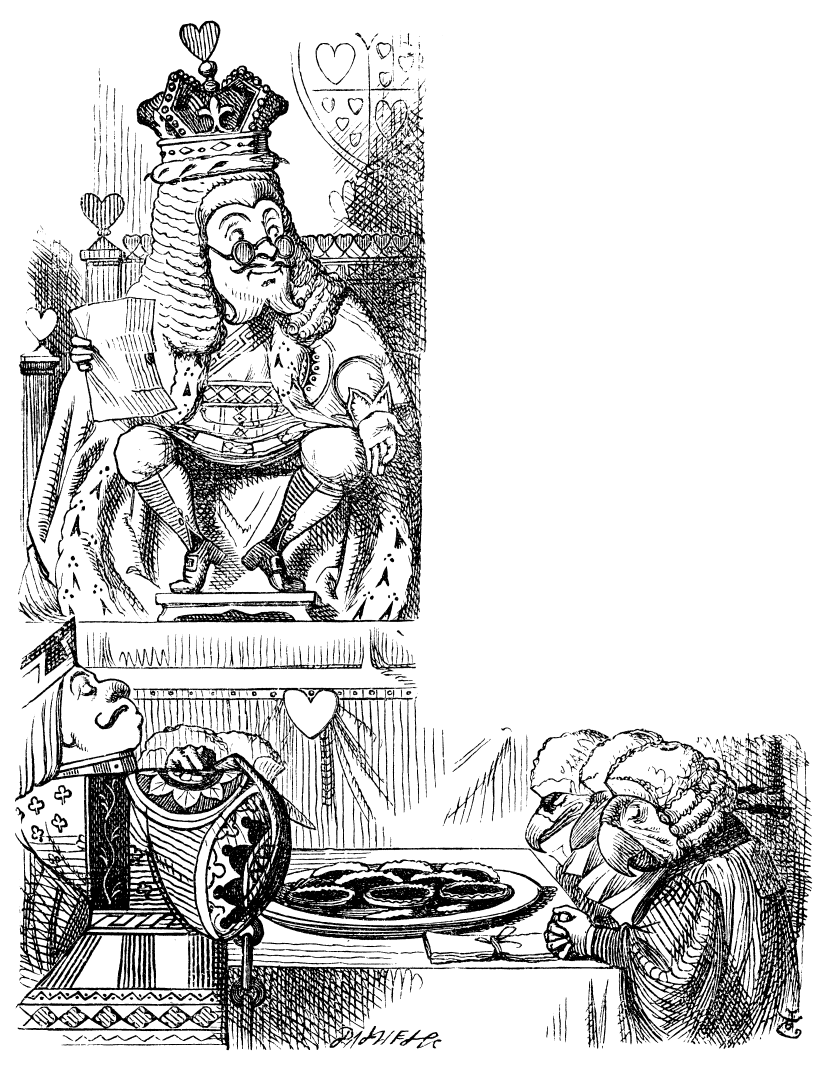

'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—ALL,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do.

— Il processo, — disse il Re con voce grave, — non può andare innanzi se tutti i giurati non saranno al loro posto... dico tutti, — soggiunse con energia, guardando fisso Alice.

Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be QUITE as much use in the trial one way up as the other.'

Alice guardò il banco de’ giurati, e vide che nella fretta avea rimessa la lucertola a testa in giù. La poverina agitava melanconicamente la coda, non potendosi muovere. Subito la raddrizzò. "Non già perchè significhi qualche cosa, — disse fra sè, — perchè ne la testa nè la coda gioveranno al processo."

As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court.

Appena i giurati si furono rimessi dalla caduta e riebbero in consegna le lavagne e le matite, si misero a scarabocchiare con molta ansia la storia del loro ruzzolone, tranne la lucertola, che era ancora stordita e sedeva a bocca spalancata, guardando il soffitto.

'What do you know about this business?' the King said to Alice.

— Che cosa sai di quest’affare? — domandò il Re ad Alice.

'Nothing,' said Alice.

— Niente, — rispose Alice.

'Nothing WHATEVER?' persisted the King.

— Proprio niente? — replicò il Re.

'Nothing whatever,' said Alice.

— Proprio niente, — soggiunse Alice.

'That's very important,' the King said, turning to the jury. They were just beginning to write this down on their slates, when the White Rabbit interrupted: 'UNimportant, your Majesty means, of course,' he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning and making faces at him as he spoke.

— È molto significante, — disse il Re, volgendosi ai giurati.

Essi si accingevano a scrivere sulle lavagne, quando il Coniglio bianco li interruppe:

— Insignificante, intende certamente vostra Maestà, — disse con voce rispettosa, ma aggrottando le ciglia e facendo una smorfia mentre parlava.

'UNimportant, of course, I meant,' the King hastily said, and went on to himself in an undertone, 'important—unimportant—unimportant—important—' as if he were trying which word sounded best.

— Insignificante, già, è quello che intendevo — soggiunse in fretta il Re; e poi si mise a dire a bassa voce: "significante, insignificante, significante..." — come se volesse provare quale delle due parole sonasse meglio.

Some of the jury wrote it down 'important,' and some 'unimportant.' Alice could see this, as she was near enough to look over their slates; 'but it doesn't matter a bit,' she thought to herself.

Alcuni dei giurati scrissero "significante", altri "insignificante."

Alice potè vedere perchè era vicina, e poteva sbirciare sulle lavagne: "Ma non importa", pensò.

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busily writing in his note-book, cackled out 'Silence!' and read out from his book, 'Rule Forty-two. ALL PERSONS MORE THAN A MILE HIGH TO LEAVE THE COURT.'

Allora il Re, che era stato occupatissimo a scrivere nel suo taccuino, gridò: — Silenzio! — e lesse dal suo libriccino: "Norma quarantaduesima: — Ogni persona, la cui altezza supera il miglio deve uscire dal tribunale." Tutti guardarono Alice.

Everybody looked at Alice.

— Io non sono alta un miglio, — disse Alice.

'I'M not a mile high,' said Alice.

— Sì che lo sei, — rispose il Re.

'You are,' said the King.

— Quasi due miglia d’altezza, — aggiunse la Regina.

'Nearly two miles high,' added the Queen.

— Ebbene non m’importa, ma non andrò via, — disse Alice. — Inoltre quella è una norma nuova; l’avete inventata or ora.

'Well, I shan't go, at any rate,' said Alice: 'besides, that's not a regular rule: you invented it just now.'

— Che! è la più vecchia norma del libro! — rispose il Re.

'It's the oldest rule in the book,' said the King.

— Allora dovrebbe essere la prima, — disse Alice.

'Then it ought to be Number One,' said Alice.

Allora il Re diventò pallido e chiuse in fretta il libriccino.

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily. 'Consider your verdict,' he said to the jury, in a low, trembling voice.

— Ponderate il vostro verdetto, — disse volgendosi ai giurati, ma con voce sommessa e tremante.

'There's more evidence to come yet, please your Majesty,' said the White Rabbit, jumping up in a great hurry; 'this paper has just been picked up.'

— Maestà, vi sono altre testimonianze, — disse il Coniglio bianco balzando in piedi. — Giusto adesso abbiamo trovato questo foglio.

'What's in it?' said the Queen.

— Che contiene? — domandò la Regina

'I haven't opened it yet,' said the White Rabbit, 'but it seems to be a letter, written by the prisoner to—to somebody.'

Non l’ho aperto ancora, disse il Coniglio bianco; — ma sembra una lettera scritta dal prigioniero a... a qualcuno.

'It must have been that,' said the King, 'unless it was written to nobody, which isn't usual, you know.'

— Dev’essere così — disse il Re, — salvo che non sia stata scritta a nessuno, il che generalmente non avviene.

'Who is it directed to?' said one of the jurymen.

— A chi è indirizzata — domandò uno dei giurati.

'It isn't directed at all,' said the White Rabbit; 'in fact, there's nothing written on the OUTSIDE.' He unfolded the paper as he spoke, and added 'It isn't a letter, after all: it's a set of verses.'

— Non ha indirizzo, — disse il Coniglio bianco, — infatti non c’è scritto nulla al di fuori. — E aprì il foglio mentre parlava, e soggiunse: — Dopo tutto, non è una lettera; è una filastrocca in versi.

'Are they in the prisoner's handwriting?' asked another of the jurymen.

— Sono di mano del prigioniero? — domandò un giurato.

'No, they're not,' said the White Rabbit, 'and that's the queerest thing about it.' (The jury all looked puzzled.)

— No, no, —rispose Il Coniglio bianco, questo è ancora più strano. (I giurati si guardarono confusi.)

'He must have imitated somebody else's hand,' said the King. (The jury all brightened up again.)

— Forse ha imitato la scrittura di qualcun altro, — disse il Re.(I giurati si schiarirono.)

'Please your Majesty,' said the Knave, 'I didn't write it, and they can't prove I did: there's no name signed at the end.'

— Maestà, — disse il Fante, — io non li ho scritti, e nessuno potrebbe provare il contrario. E poi non c’è alcuna firma in fondo.

'If you didn't sign it,' said the King, 'that only makes the matter worse. You MUST have meant some mischief, or else you'd have signed your name like an honest man.'

— Il non aver firmato, — rispose il Re, non fa che aggravare il tuo delitto. Tu miravi certamente a un reato; se no, avresti lealmente firmato il foglio.

There was a general clapping of hands at this: it was the first really clever thing the King had said that day.

Vi fu un applauso generale, e a ragione, perchè quella era la prima frase di spirito detta dal Re in quel giorno.

'That PROVES his guilt,' said the Queen.

— Questo prova la sua colpa, — affermò la Regina.

'It proves nothing of the sort!' said Alice. 'Why, you don't even know what they're about!'

— Non prova niente, — disse Alice. — Ma se non sai neppure ciò che contiene il foglio!

'Read them,' said the King.

— Leggilo! — disse il re.

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. 'Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?' he asked.

Il Coniglio bianco si mise gli occhiali e domandò: — Maestà, di grazia, di dove debbo incominciare ?

'Begin at the beginning,' the King said gravely, 'and go on till you come to the end: then stop.'

— Comincia dal principio, — disse il Re solennemente... — e continua fino alla fine, poi fermati.

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:—

Or questi erano i versi che il Coniglio bianco lesse:

'They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

"Mi disse che da lei te n’eri andato,

ed a lui mi volesti rammentar;

lei poi mi diede il mio certificato

dicendomi: ma tu non sai nuotar.

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

Egli poi disse che non ero andato

(e non si può negar, chi non lo sa?)

e se il negozio sarà maturato,

oh dimmi allor di te che mai sarà?

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

Una a lei diedi, ed essi due le diero,

tu me ne desti tre, fors’anche più;

ma tutte si rinvennero, — o mistero!

ed eran tutte mie, non lo sai tu?

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

Se lei ed io per caso in questo affare

misterioso involti ci vedrem,

egli ha fiducia d’esser liberato

e con noi stare finalmente insiem.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

Ho questa idea che prima dell’accesso,

(già tu sai che un accesso la colpì),

un ostacol per lui, per noi, per esso

fosti tu solo in quel fatale dì.

Don't let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.'

Ch’egli non sappia chi lei predilige

(il segreto bisogna mantener);

sia segreto per tutti, chè qui vige

la impenetrabile legge del mister."

'That's the most important piece of evidence we've heard yet,' said the King, rubbing his hands; 'so now let the jury—'

— Questo è il più importante documento di accusa, — disse il Re stropicciandosi le mani; — ora i giurati si preparino.

'If any one of them can explain it,' said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn't a bit afraid of interrupting him,) 'I'll give him sixpence. I don't believe there's an atom of meaning in it.'

— Se qualcuno potesse spiegarmelo, — disse Alice (la quale era talmente cresciuta in quegli ultimi minuti che non aveva più paura d’interrompere il Re) — gli darei mezza lira. Non credo che ci sia in esso neppure un atomo di buon senso.

The jury all wrote down on their slates, 'SHE doesn't believe there's an atom of meaning in it,' but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

I giurati scrissero tutti sulla lavagna: "Ella non crede che vi sia in esso neppure un atomo di buon senso". Ma nessuno cercò di spiegare il significato del foglio.

'If there's no meaning in it,' said the King, 'that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn't try to find any. And yet I don't know,' he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; 'I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. "—SAID I COULD NOT SWIM—" you can't swim, can you?' he added, turning to the Knave.

— Se non c’è un significato, — disse il Re, — noi usciamo da un monte di fastidi, perchè non è necessario trovarvelo. E pure non so, — continuò aprendo il foglio sulle ginocchia e sbirciandolo, — ma mi pare di scoprirvi un significato, dopo tutto... "Disse... non sai mica nuotar." Tu non sai nuotare, non è vero? — continuò volgendosi al Fante.

The Knave shook his head sadly. 'Do I look like it?' he said. (Which he certainly did NOT, being made entirely of cardboard.)

Il Fante scosse tristemente la testa e disse: — Vi pare che io possa nuotare? (E certamente, no, perchè era interamente di cartone).

'All right, so far,' said the King, and he went on muttering over the verses to himself: '"WE KNOW IT TO BE TRUE—" that's the jury, of course—"I GAVE HER ONE, THEY GAVE HIM TWO—" why, that must be what he did with the tarts, you know—'

— Bene, fin qui,—, disse il Re, e continuò: — "E questo è il vero, e ognun di noi io sa." Questo è senza dubbio per i giurati. — "Una a lei diedi, ed essi due gli diero." — Questo spiega l’uso fatto delle torte, capisci...

'But, it goes on "THEY ALL RETURNED FROM HIM TO YOU,"' said Alice.

Ma, — disse Alice, — continua con le parole: "Ma tutte si rinvennero."

'Why, there they are!' said the King triumphantly, pointing to the tarts on the table. 'Nothing can be clearer than THAT. Then again—"BEFORE SHE HAD THIS FIT—" you never had fits, my dear, I think?' he said to the Queen.

— Già, esse son la, —disse il Re con un’aria di trionfo, indicando le torte sul tavolo. — Nulla di più chiaro. Continua:"Già tu sai che un accesso la colpì",— tu non hai mai avuto degli attacchi nervosi, cara mia, non è vero?— soggiunse volgendosi alla Regina.

'Never!' said the Queen furiously, throwing an inkstand at the Lizard as she spoke. (The unfortunate little Bill had left off writing on his slate with one finger, as he found it made no mark; but he now hastily began again, using the ink, that was trickling down his face, as long as it lasted.)

— Mai! — gridò furiosa la Regina, e scaraventò un calamaio sulla testa della lucertola. (Il povero Guglielmo! aveva cessato di scrivere sulla lavagna col dito, perchè s’era accorto che non ne rimaneva traccia; e in quell’istante si rimise sollecitamente all’opera, usando l’inchiostro che gli scorreva sulla faccia, e l’usò finche ne ebbe.)

'Then the words don't FIT you,' said the King, looking round the court with a smile. There was a dead silence.

— Dunque a te questo verso non si attacca, — disse il Re, guardando con un sorriso il tribunale. E vi fu gran silenzio.

'It's a pun!' the King added in an offended tone, and everybody laughed, 'Let the jury consider their verdict,' the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

È un bisticcio — soggiunse il Re con voce irata, e tutti allora risero. — Che i giurati ponderino il loro verdetto — ripetè il Re, forse per la ventesima volta quel giorno.

'No, no!' said the Queen. 'Sentence first—verdict afterwards.'

— No, disse la Regina. — Prima la sentenza, poi il verdetto.

'Stuff and nonsense!' said Alice loudly. 'The idea of having the sentence first!'

— È una stupidità — esclamò Alice. — Che idea d’aver prima la sentenza!

'Hold your tongue!' said the Queen, turning purple.

— Taci! — gridò la Regina, tutta di porpora in viso.

'I won't!' said Alice.

— Ma che tacere! — disse Alice.

'Off with her head!' the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

— Tagliatele la testa! urlò la Regina con quanta voce aveva. Ma nessuno si mosse.

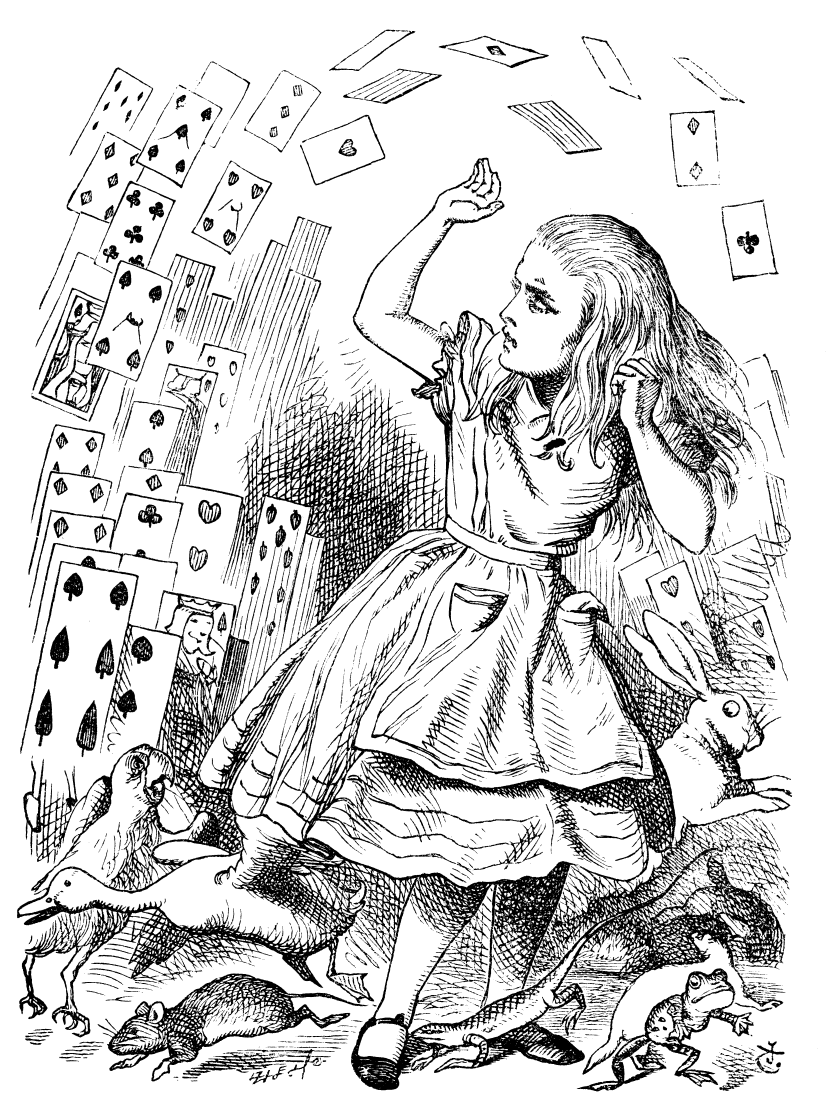

'Who cares for you?' said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) 'You're nothing but a pack of cards!'

— Chi si cura di te? — disse Alice, (allora era cresciuta fino alla sua statura naturale.); — Tu non sei che la Regina d’un mazzo di carte.

At this the whole pack rose up into the air, and came flying down upon her: she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

A queste parole tutto il mazzo si sollevò in aria vorticosamente e poi si rovesciò sulla fanciulla: essa diede uno strillo di paura e d’ira, e cercò di respingerlo da sè, ma si trovò sul poggio, col capo sulle ginocchia di sua sorella, la quale le toglieva con molta delicatezza alcune foglie secche che le erano cadute sul viso.

'Wake up, Alice dear!' said her sister; 'Why, what a long sleep you've had!'

— Risvegliati, Alice cara,— le disse la sorella, — da quanto tempo dormi, cara!

'Oh, I've had such a curious dream!' said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers that you have just been reading about; and when she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said, 'It WAS a curious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it's getting late.' So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.

— Oh! ho avuto un sogno così curioso! — disse Alice, e raccontò alla sorella come meglio potè, tutte le strane avventure che avete lette; e quando finì, la sorella la baciò e le disse:

— È stato davvero un sogno curioso, cara ma ora, va subito a prendere il tè; è già tardi. — E così Alice si levò; e andò via, pensando, mentre correva, al suo sogno meraviglioso.

But her sister sat still just as she left her, leaning her head on her hand, watching the setting sun, and thinking of little Alice and all her wonderful Adventures, till she too began dreaming after a fashion, and this was her dream:—

Sua sorella rimase colà con la testa sulla palma, tutta intenta a guardare il sole al tramonto, pensando alla piccola Alice, e alle sue avventure meravigliose finchè anche lei si mise a sognare, e fece un sogno simile a questo:

First, she dreamed of little Alice herself, and once again the tiny hands were clasped upon her knee, and the bright eager eyes were looking up into hers—she could hear the very tones of her voice, and see that queer little toss of her head to keep back the wandering hair that WOULD always get into her eyes—and still as she listened, or seemed to listen, the whole place around her became alive with the strange creatures of her little sister's dream.

Prima di tutto sognò la piccola, Alice, con le sue manine delicate congiunte sulle ginocchia di lei e coi grandi occhioni lucenti fissi in lei. Le sembrava di sentire il vero suono della sua voce, e di vedere quella caratteristica mossa della sua testolina quando rigettava indietro i capelli che volevano velarle gli occhi. Mentre ella era tutta intenta ad ascoltare, o sembrava che ascoltasse, tutto il. luogo d’intorno si popolò delle strane creature del sogno di sua sorella.

The long grass rustled at her feet as the White Rabbit hurried by—the frightened Mouse splashed his way through the neighbouring pool—she could hear the rattle of the teacups as the March Hare and his friends shared their never-ending meal, and the shrill voice of the Queen ordering off her unfortunate guests to execution—once more the pig-baby was sneezing on the Duchess's knee, while plates and dishes crashed around it—once more the shriek of the Gryphon, the squeaking of the Lizard's slate-pencil, and the choking of the suppressed guinea-pigs, filled the air, mixed up with the distant sobs of the miserable Mock Turtle.

L’erba rigogliosa stormiva ai suoi piedi, mentre il Coniglio passava trotterellando e il Topo impaurito s’apriva a nuoto una via attraverso lo stagno vicino. Ella poteva sentire il rumore delle tazze mentre la Lepre di Marzo e gli amici suoi partecipavano al pasto perpetuo; udiva la stridula voce della Regina che mandava i suoi invitati a morte. Ancora una volta il bimbo Porcellino starnutiva sulle ginocchia della Duchessa, mentre i tondi e i piatti volavano e s’infrangevano d’intorno e l’urlo del Grifone, lo stridore della matita della Lucertola sulla lavagna, la repressione dei Porcellini d’India riempivano l’aria misti ai singhiozzi lontani della Falsa-testuggine.

So she sat on, with closed eyes, and half believed herself in Wonderland, though she knew she had but to open them again, and all would change to dull reality—the grass would be only rustling in the wind, and the pool rippling to the waving of the reeds—the rattling teacups would change to tinkling sheep-bells, and the Queen's shrill cries to the voice of the shepherd boy—and the sneeze of the baby, the shriek of the Gryphon, and all the other queer noises, would change (she knew) to the confused clamour of the busy farm-yard—while the lowing of the cattle in the distance would take the place of the Mock Turtle's heavy sobs.

Si sedette, con gli occhi a metà velati e quasi si credè davvero nel Paese delle Meraviglie; benchè sapesse che aprendo gli occhi tutto si sarebbe mutato nella triste realtà. Avrebbe sentito l’erba stormire al soffiar del vento, avrebbe veduto lo stagno incresparsi all’ondeggiare delle canne. L’acciottolio, delle tazze si sarebbe mutato nel tintinnio della campana delle pecore, e la stridula voce della Regina nella voce del pastorello, e gli starnuti del bimbo, l’urlo del Grifone e tutti gli altri curiosi rumori si sarebbero mutati (lei lo sapeva) nel rumore confuso d’una fattoria, e il muggito lontano degli armenti avrebbe sostituito i profondi singhiozzi della Falsa-testuggine.

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make THEIR eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.

Finalmente essa immaginò come sarebbe stata la sorellina già cresciuta e diventata donna: Alice avrebbe conservato nei suoi anni maturi il cuore affettuoso e semplice dell’infanzia e avrebbe raccolto intorno a sè altre fanciulle e avrebbe fatto loro risplendere gli occhi, beandole con molte strane storielle e forse ancora col suo sogno di un tempo: le sue avventure nel Paese delle Meraviglie. Con quanta tenerezza avrebbe ella stessa partecipato alle loro innocenti afflizioni, e con quanta gioia alle loro gioie, riandando i beati giorni della infanzia e le felici giornate estive!

THE END

FINE

Audio from LibreVox.org

Narration by Silvia Cecchini