ALENKA V ŘÍŠI DIVŮ

All in the golden afternoon

Full leisurely we glide;

For both our oars, with little skill,

By little arms are plied,

While little hands make vain pretence

Our wanderings to guide.

Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour.

Beneath such dreamy weather.

To beg a tale of breath too weak

To stir the tiniest feather!

Yet what can one poor voice avail

Against three tongues together?

Imperious Prima flashes forth

Her edict "to begin it"—

In gentler tone Secunda hopes

"There will he nonsense in it!"—

While Tertia interrupts the tale

Not more than once a minute.

Anon, to sudden silence won,

In fancy they pursue

The dream-child moving through a land

Of wonders wild and new,

In friendly chat with bird or beast—

And half believe it true.

And ever, as the story drained

The wells of fancy dry,

And faintly strove that weary one

To put the subject by,

"The rest next time—" "It is next time!"

The happy voices cry.

Thus grew the tale of Wonderland:

Thus slowly, one by one,

Its quaint events were hammered out—

And now the tale is done,

And home we steer, a merry crew,

Beneath the setting' sun.

Alice! a childish story take,

And with a gentle hand

Lay it where Childhood's dreams are twined

In Memory's mystic band,

Like pilgrim's wither'd wreath of flowers

Pluck'd in a far-off land.

1

CHAPTER I.

DO KRÁLIČÍ NORY

Down the Rabbit-Hole

Alenka - dokud ještěbyla s rodiči ve své rodné Anglii, říkali jí Alice - už začínala mít dost toho nečinného sedění vedle sestry na břehu řeky: jednou nebo dvakrát nahlédla do knížky, kterou sestra četla, ale tam nebyly vůbec žádné obrázky nebo rozmluvy - "a co je po knížce," myslila si Alenka, "ve které nejsou obrázky, ba ani rozmluvy?"

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, 'and what is the use of a book,' thought Alice 'without pictures or conversation?'

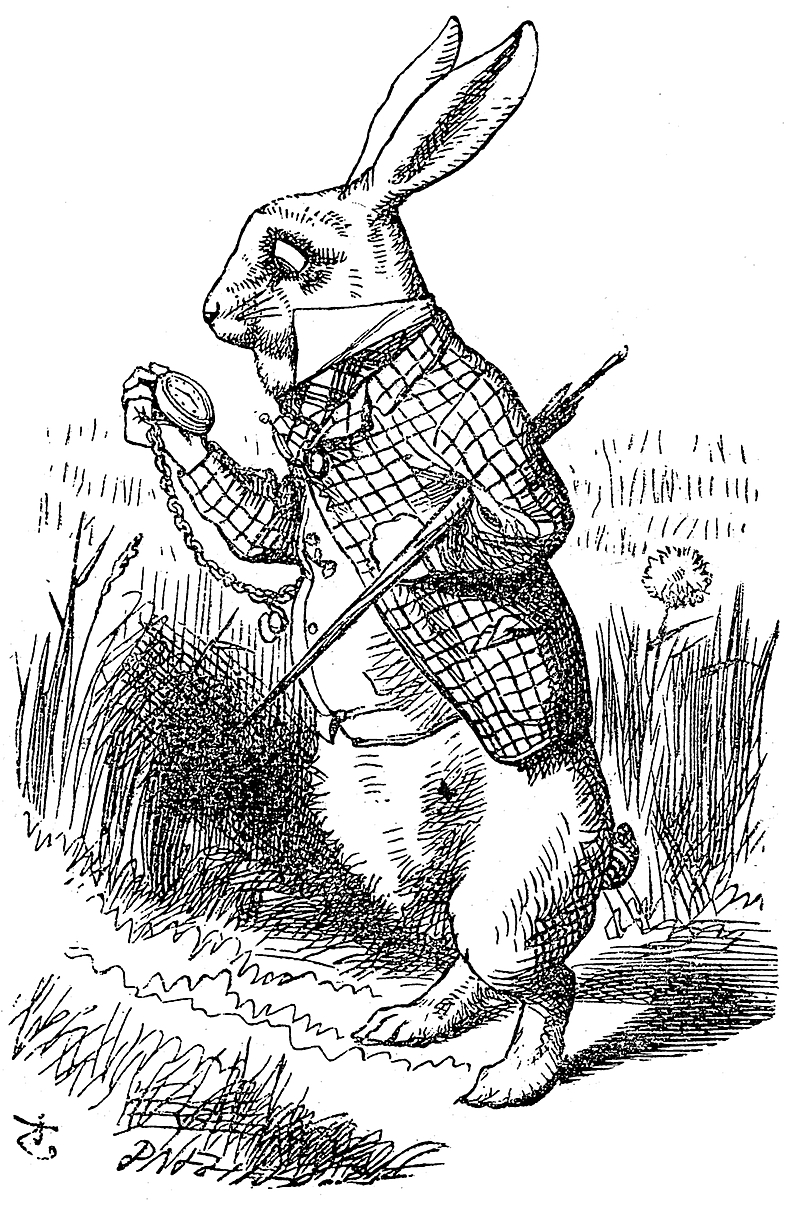

Přemýšlela tedy - jak nejlépe mohla, neboťbyl horký den, a to ji dělalo ospalou. a hloupou - stojí-li pěkný věneček za to, aby vstala a sbírala květinky, když tu náhle kolem ní přeběhl Bílý Králík s červenýma očima.

So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

V tom nebylo nic tak velmi podivuhodného; a Alenka v tom neviděla nic tak velmi zvláštního, ani když slyšela, jak si Králík k sobě říká: "Bože, bože! Bože, bože! Já jistěpřijdu pozdě!" (Když o tom přemýšlela později, napadlo jí, že se nad tím měla pozastavit; v tu chvíli se jí to však zdálo docela přirozené.) Ale když Králík skutečněvytáhl hodinky z kapsičky u vesty, podíval se na něa pospíchal dále, vyskočila Alenka údivem, neboťjí prolétlo hlavou, že nikdy předtím neviděla králíka, který by měl kapsičku u vesty, neřkuli hodinky, které by z ní mohl vytáhnout; a hoříc zvědavostí, běžela za ním přes pole a naštěstí doběhla ještěvčas, aby viděla, jak vskočil do velké králičí díry pod mezí.

There was nothing so VERY remarkable in that; nor did Alice think it so VERY much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself, 'Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!' (when she thought it over afterwards, it occurred to her that she ought to have wondered at this, but at the time it all seemed quite natural); but when the Rabbit actually TOOK A WATCH OUT OF ITS WAISTCOAT-POCKET, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet, for it flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it, and burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it, and fortunately was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge.

Alenka ani chvíli nemeškala a vskočila za ním, aniž jen zdaleka pomyslila, jak se kdy opět dostane ven.

In another moment down went Alice after it, never once considering how in the world she was to get out again.

Králičí díra vedla zpočátku přímo jako tunel a pak se za hnula dolů; tak náhle, že než mohla Alenka uvážit, nemá-li zastavit, shledala, že padá do jakési velmi hluboké studny.

The rabbit-hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down a very deep well.

Buďbyla ta studna velmi hluboká, anebo Alenkapadala velmi zvolna, neboť měla při tom padání dosti času, aby se ohlížela kolem sebe a uvažovala, co se stane dále. Zprvu se pokoušela podívat se dolů pod sebe, aby se přesvědčila, kam padá, ale bylo příliš temno, než aby něco viděla. Začala se tedy ohlížeti po stěnách studny a zpozorovala, že jsou na ní samé kuchyňské police a přihrádky na knihy; tu a tam visely na hřebíku mapy a obrazy. Jak letěla mimo, vzala si z jedné poličky skleničku s nálepkou: MERUŇKOVÁ MARMELÁDA; avšak k jejímu velkému zklamání byla sklenička prázdná. Nechtěla ji zahodit ze strachu, že by mohla někoho zabít, tak se jí podařilo postavit ji zase na jednu poličku, podle níž padala.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next. First, she tried to look down and make out what she was coming to, but it was too dark to see anything; then she looked at the sides of the well, and noticed that they were filled with cupboards and book-shelves; here and there she saw maps and pictures hung upon pegs. She took down a jar from one of the shelves as she passed; it was labelled 'ORANGE MARMALADE', but to her great disappointment it was empty: she did not like to drop the jar for fear of killing somebody, so managed to put it into one of the cupboards as she fell past it.

- "Nu," pomyslila si Alenka, "po takovémhle pádu si z toho už nic nebudu dělat, spadnu-li doma ze schodů! To se budou doma divit, jak jsem statečná! Hm, teďbych už neřekla nic, ani kdybych spadla ze střechy!" (Což bylo velmi podobné pravdě.)

'Well!' thought Alice to herself, 'after such a fall as this, I shall think nothing of tumbling down stairs! How brave they'll all think me at home! Why, I wouldn't say anything about it, even if I fell off the top of the house!' (Which was very likely true.)

Dolů, dolů, dolů! Nebude tomu padání nikdy konce? "To bych ráda věděla, kolik mil už jsem proletěla," řekla nahlas. "Musím se už blížit středu Země. Počkejme: to by bylo, myslím, 4000 mil..." (jak vidíte, Alenka se ve škole naučila celé řadětakovýchhle věcí, a ačkoli toto nebyla zrovna nejlepší příležitost, aby se blýskala svými vědomostmi, jelikož tu nebylo nikoho, kdo by ji poslouchal, přece si myslila, že je dobře něco si zopakovat) - "ano, to bude tak asi správná vzdálenost, ale pak bych ráda věděla, na kterém jsem se to octla stupni zeměpisné šířky a délky?" (Jak vidíte, Alenka neměla ponětí, co je to zeměpisná šířka a délka, myslila si však, že jsou to krásná velká slova a že se vyjadřuje učeně.)

Down, down, down. Would the fall NEVER come to an end! 'I wonder how many miles I've fallen by this time?' she said aloud. 'I must be getting somewhere near the centre of the earth. Let me see: that would be four thousand miles down, I think—' (for, you see, Alice had learnt several things of this sort in her lessons in the schoolroom, and though this was not a VERY good opportunity for showing off her knowledge, as there was no one to listen to her, still it was good practice to say it over) '—yes, that's about the right distance—but then I wonder what Latitude or Longitude I've got to?' (Alice had no idea what Latitude was, or Longitude either, but thought they were nice grand words to say.)

Po chvíli začala opět: "To jsem zvědavá, zdali proletím skrz celou Zemi! To bude legrace, až vyletím mezi lidi, kteří chodí vzhůru nohama! Jakpak se jim jen říká... antipatové, myslím" - (jak vidíte, zaslechla kdysi, že se protinožcům říká antipodové, a špatněsi to zapamatovala; ani jí samotné to však neznělo správněa byla, panečku, ráda, že ji tentokrát nikdo neposlouchal, protože je to velká ostuda, blýskat se cizími slovy a neumět jich. užívat) - "ale to se jich budu muset zeptat, jak se ta země, kde vypadnu, jmenuje. Prosím, milostivá paní, jsem to na Novém Zélandě, nebo v Austrálii?" (A pokusila se při tom oslovení o zdvořilou poklonku; jen si představte, jak děláte poklonku, padajíce z třetího patra! Myslíte, že byste to dovedli?) "A za jak hloupou malou holčičku mne budou mít! Ne, to nepůjde, ptát se; snad to někde uvidím napsáno.

Presently she began again. 'I wonder if I shall fall right THROUGH the earth! How funny it'll seem to come out among the people that walk with their heads downward! The Antipathies, I think—' (she was rather glad there WAS no one listening, this time, as it didn't sound at all the right word) '—but I shall have to ask them what the name of the country is, you know. Please, Ma'am, is this New Zealand or Australia?' (and she tried to curtsey as she spoke—fancy CURTSEYING as you're falling through the air! Do you think you could manage it?) 'And what an ignorant little girl she'll think me for asking! No, it'll never do to ask: perhaps I shall see it written up somewhere.'

Dolů, dolů, dolů. Nic jiného se nedalo dělat, Alenka tedy brzy začala znovu mluvit. "Minda se po mnějistědnes bude shánět!" (Minda byla Alenčina kočka.) "Doufám, že nezapomenou při svačiněna její misku mléka. Mindo, drahoušku, kéž bys tu byla dole se mnou! Ve vzduchu sice, myslím, nejsou žádné myši, ale mohla bys tuchytit netopýra a to, víš, je skoro jako myš. - Ale jedí vůbec kočky netopýry?" A tu začala být Alenka trochu ospalá a počala si odříkávat: "Jedí kočky netopýry? Jedí netopýry kočky?" a někdy: "Jedí netopýři kočky?" a1e jelikož, jak vidíte, nedovedla odpovědět ani na jednu, ani na druhou otázku, bylo to celkem jedno, jak ji položila. Cítila, že usíná, a právěse jí začalo zdát, že se vede za ruku s Mindou a ptá se jí velmi vážně: "Nuže, Mindo, řekni mi pravdu, jedlas někdy netopýra?" - když tu najednou buch! - dopadla na hromadu suchého listí a bylo po pádu.

Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again. 'Dinah'll miss me very much to-night, I should think!' (Dinah was the cat.) 'I hope they'll remember her saucer of milk at tea-time. Dinah my dear! I wish you were down here with me! There are no mice in the air, I'm afraid, but you might catch a bat, and that's very like a mouse, you know. But do cats eat bats, I wonder?' And here Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, 'Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?' and sometimes, 'Do bats eat cats?' for, you see, as she couldn't answer either question, it didn't much matter which way she put it. She felt that she was dozing off, and had just begun to dream that she was walking hand in hand with Dinah, and saying to her very earnestly, 'Now, Dinah, tell me the truth: did you ever eat a bat?' when suddenly, thump! thump! down she came upon a heap of sticks and dry leaves, and the fall was over.

Alenka si ani trochu neublížila a v mžiku byla na nohou: pohlédla nad sebe a kolem sebe, nad ní bylo temno a před ní nová dlouhá chodba, v níž ještězahlédla pospíchajícího Bílého Králíka. Nesměla ztratit ani vteřinu: jako vítr se pustila za ním a doběhla k němu dosti blízko, aby slyšela, jak si povídá, zahýbajekolem rohu: "U mých uší a vousů, jak je pozdě!" Byla těsněza ním, když zahnula kolem rohu. Králík se jí však náhle ztratil z očí. Byla v dlouhé nízké síni, osvětlené řadou lamp, visících ze stropu.

Alice was not a bit hurt, and she jumped up on to her feet in a moment: she looked up, but it was all dark overhead; before her was another long passage, and the White Rabbit was still in sight, hurrying down it. There was not a moment to be lost: away went Alice like the wind, and was just in time to hear it say, as it turned a corner, 'Oh my ears and whiskers, how late it's getting!' She was close behind it when she turned the corner, but the Rabbit was no longer to be seen: she found herself in a long, low hall, which was lit up by a row of lamps hanging from the roof.

Po obou stranách síněbyly řady dveří, všechny však byly zamčeny, a když je Alenka všechny po jedné i po druhé straněvyzkoušela, ubírala se smutněprostředkem síněpřemýšlejíc, jak se kdy opět dostane domů.

There were doors all round the hall, but they were all locked; and when Alice had been all the way down one side and up the other, trying every door, she walked sadly down the middle, wondering how she was ever to get out again.

Pojednou jí stál v cestěmalý třínohý stolek, celý z hladkého průhledného skla; na něm nebylo nic než malinký zlatý klíček, a Alenku hned napadlo, že by to mohl být klíček od některých těch dveří: ale běda! buď byly zámky příliš velké, nebo klíčpříliš malý, aťuž tak nebo onak, nehodily se k sobě. Když však tak po druhé obcházela, uviděla před sebou nízkou záclonku, které dříve nezpozorovala, a za ní byly malé dveře, tak asi patnáct palcůvysoké: zkusila zlatý klíček v jejich zámku a k veliké její radosti zapadl.

Suddenly she came upon a little three-legged table, all made of solid glass; there was nothing on it except a tiny golden key, and Alice's first thought was that it might belong to one of the doors of the hall; but, alas! either the locks were too large, or the key was too small, but at any rate it would not open any of them. However, on the second time round, she came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high: she tried the little golden key in the lock, and to her great delight it fitted!

Alenka otevřela dveře a shledala, že vedou do malé chodbičky, ne prostornější než myší díra. Poklekla a hleděla chodbičkou do nejrozkošnější zahrady, jakou si jen můžete představit. Ó, jak toužila dostat se z malé síněa procházeti se mezi záhony zářivých květin a chladnými vodotrysky! Ale dveřmi jí neprošla ani hlava. "A kdyby mi hlava prošla," pomyslila si ubohá Alenka, "co by mi to bylo platno, když by neprošla ramena? Ó, jak bych si přála, abych se mohla stáhnoutjako dalekohled! Myslím, že bych to dovedla, jen kdybych věděla, jak začít." V poslední době, jak jste viděli, se událo tolik mimořádných věcí, že se Alenka začala domnívati, že je velmi málo věcí opravdu nemožných.

Alice opened the door and found that it led into a small passage, not much larger than a rat-hole: she knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw. How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and those cool fountains, but she could not even get her head through the doorway; 'and even if my head would go through,' thought poor Alice, 'it would be of very little use without my shoulders. Oh, how I wish I could shut up like a telescope! I think I could, if I only know how to begin.' For, you see, so many out-of-the-way things had happened lately, that Alice had begun to think that very few things indeed were really impossible.

Čekati u malých dvířek se jí zdálo bezúčelné, vrátila se tedy ke stolku, napolo doufajíc, že na něm nalezne nový klíčnebo aspoňknížku návodů, podle nichž by se člověk mohl stáhnout jako dalekohled; a tenkrát tu nalezla lahvičku ("která tu před chvílí zcela určitěnebyla," řekla si Alenka) a na té byla přivázána cedulka, na níž bylo velikými písmeny krásněvytištěno: VYPIJ MNE!

There seemed to be no use in waiting by the little door, so she went back to the table, half hoping she might find another key on it, or at any rate a book of rules for shutting people up like telescopes: this time she found a little bottle on it, ('which certainly was not here before,' said Alice,) and round the neck of the bottle was a paper label, with the words 'DRINK ME' beautifully printed on it in large letters.

- To se pěkně řekne: "Vypij mne!" - tohle však moudrá Alenka neudělá tak náhle. - "Ne, napřed se podíváme," řekla si, "není-li na tom nálepka s nápisem JED!" neboť četla mnoho povídek o dětech, které se spálily, nebo byly snědeny divou zvěří, nebo kterým se stalo mnoho jiných nepříjemných věcí, a to všechno jen proto, že ne a ne, aby si pamatovaly jednoduché poučky, kterým je učili jejich přátelé: například, že se možno spálit rozžhaveným háčkem, držíme-li jej v ruce příliš dlouho, nebo že prst obyčejněkrvácí, řízneme-li do něho nožem příliš hluboko; a ni kdy nezapomněla, že, napijeme-li se z lahvičky, na které je napsáno JED! - je skorem jisto, že toho dříve či později budeme litovat.

It was all very well to say 'Drink me,' but the wise little Alice was not going to do THAT in a hurry. 'No, I'll look first,' she said, 'and see whether it's marked "poison" or not'; for she had read several nice little histories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts and other unpleasant things, all because they WOULD not remember the simple rules their friends had taught them: such as, that a red-hot poker will burn you if you hold it too long; and that if you cut your finger VERY deeply with a knife, it usually bleeds; and she had never forgotten that, if you drink much from a bottle marked 'poison,' it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.

Na této lahvičce však nebylo napsáno JED! a tak se Alenka odvážila okusit jejího obsahu; a shledavši jej docela chutným (měl totiž jakousi smíšenou chuťtřešňového koláče, krupičné kaše, ananasu, pečené husy, čokolády a topinky s máslem), byla s lahvičkou brzo hotova.

However, this bottle was NOT marked 'poison,' so Alice ventured to taste it, and finding it very nice, (it had, in fact, a sort of mixed flavour of cherry-tart, custard, pine-apple, roast turkey, toffee, and hot buttered toast,) she very soon finished it off.

"Jaký to podivný pocit!" řekla Alenka. "Jistěse do sebe zatahuji jako dalekohled."

'What a curious feeling!' said Alice; 'I must be shutting up like a telescope.'

A tak tomu opravdu bylo: byla teďjen deset palcůvysoká a tvářse jí vyjasnila při pomyšlení, že má nyní zrovna potřebnou míru, aby mohla projít malými vrátky do krásné zahrady. Nejprve však několik minut čekala, záhy zjistila, nezkracuje-li se ještě dále; trochu jí to působilo starost; "neboťto by, víte, mohlo skončit tím" - řekla si - "že bych se zkrátila v nic, jako dohořelá svíčka. To bych ráda věděla, jak bych potom vypadala!" a pokoušela se představit si, jak vypadá plamen svíčky po zhasnuti, neboťse nedovedla upamatovati, že by kdy co takového byla viděla.

And so it was indeed: she was now only ten inches high, and her face brightened up at the thought that she was now the right size for going through the little door into that lovely garden. First, however, she waited for a few minutes to see if she was going to shrink any further: she felt a little nervous about this; 'for it might end, you know,' said Alice to herself, 'in my going out altogether, like a candle. I wonder what I should be like then?' And she tried to fancy what the flame of a candle is like after the candle is blown out, for she could not remember ever having seen such a thing.

Když po chvíli zjistila, že se s ní dál nic neděje, rozhodla se, že půjde ihned do zahrady. Ale běda! Když došla ke dveřím, shledala ubohá Alenka, že zapomněla zlatý klíček, a když se proň vrátila ke stolku, zjistila, že naňnemůže nikterak dosáhnout; viděla jej zcela zřetelněsklem stolku a pokoušela se, jak nejlépe dovedla, vyšplhati se po jedné z jeho noh, ale ta byla příliš hladká; a když se ubožačka marnými pokusy úplně vyčerpala, sedla si a plakala.

After a while, finding that nothing more happened, she decided on going into the garden at once; but, alas for poor Alice! when she got to the door, she found she had forgotten the little golden key, and when she went back to the table for it, she found she could not possibly reach it: she could see it quite plainly through the glass, and she tried her best to climb up one of the legs of the table, but it was too slippery; and when she had tired herself out with trying, the poor little thing sat down and cried.

"Tak a teďdost, pláčem nic nespravíte!" řekla si k soběhodnězostra. - "Radím vám, abyste toho tu chvíli nechala!" Alenka si zpravidla dávala velmi dobré rady (ačse jimi velmi zřídka řídila) a někdy si vyhubovala tak přísně, že jí slzy vstoupily do očí; a pamatovala si, jak se jednou pokoušela napohlavkovat si za to, že se chtěla ošidit ve hře v kroket, kterou hrála sama proti sobě, neboťtoto podivné dítěsi velmi libovalo v tom, že dělalo, jako by bylo dvěma osobami. "Teďvšak není nic platno dělat, jako bych byla dvěma osobami," řekla si Alenka - "vždyťze mne zbylo sotva na jednu slušnou osobu!"

'Come, there's no use in crying like that!' said Alice to herself, rather sharply; 'I advise you to leave off this minute!' She generally gave herself very good advice, (though she very seldom followed it), and sometimes she scolded herself so severely as to bring tears into her eyes; and once she remembered trying to box her own ears for having cheated herself in a game of croquet she was playing against herself, for this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people. 'But it's no use now,' thought poor Alice, 'to pretend to be two people! Why, there's hardly enough of me left to make ONE respectable person!'

Brzy však spočinula zrakem na malé skleněné krabici, ležící pod stolem; otevřela ji a našla v ní malý koláček, na němž byla rozinkami krásněvysázená slova: SNĚZ MNE! - "Dobrá, tak těsním," řekla Alenka. "Uděláš-li mne větší, budu moci dosáhnouti klíče, a uděláš-li mne menší, podlezu pode dveřmi a tak se tím neb oním způsobem dostanu do zahrady a je mi tedy jedno, co se stane!"

Soon her eye fell on a little glass box that was lying under the table: she opened it, and found in it a very small cake, on which the words 'EAT ME' were beautifully marked in currants. 'Well, I'll eat it,' said Alice, 'and if it makes me grow larger, I can reach the key; and if it makes me grow smaller, I can creep under the door; so either way I'll get into the garden, and I don't care which happens!'

Snědla kousíček a řekla si úzkostlivě: "Kterým směrem? Kterým směrem?" - držíc si ruku na temeni hlavy, aby se přesvědčila, kterým směrem poroste. Byla velmi překvapena, shledavši, že zůstává nezměněna. Ono se to sice zpravidla tak stává, když člověk jí koláč, Alenka si však už tak zvykla očekávati samé mimořádné události, že jí obvyklý pochod života připadal hloupý a nudný.

She ate a little bit, and said anxiously to herself, 'Which way? Which way?', holding her hand on the top of her head to feel which way it was growing, and she was quite surprised to find that she remained the same size: to be sure, this generally happens when one eats cake, but Alice had got so much into the way of expecting nothing but out-of-the-way things to happen, that it seemed quite dull and stupid for life to go on in the common way.

Dala se tedy do koláče a brzy s ním byla hotova.

So she set to work, and very soon finished off the cake.

Audio from LibreVox.org